Septemvriana: A Night of Terror for Greeks in Constantinople

by Marie Lolis

Mike Katsantonis’ office is typical. His desk piled high with papers and on the floor a “We love you Pappou!” poster board from his grandchildren. Yet hanging among the family photos is the detailed drawing of the Great School of the Nation in Constantinople where he was a pupil. For Katsantonis, Constantinople (Istanbul) is not just where he spent most of his young life, but where he bore witness to Septemvriana — a pogrom that targeted the Greek population of the city. “They were saying today your material, tomorrow your lives,” Katsantonis explained.

Mike Katsantonis in his office

Sometimes compared to Kristallnacht, the pogrom took place on the night of Sept. 6, 1955 in reaction to the bombing of the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the republic of Turkiye, was allegedly born. A Greek investigation concluded a Turkish usher named Oktay Engin planted the bomb, yet Turkish media remained quiet — implying the Greeks did the bombing.

The reaction was swift. In the nine hours of terror, the mob attacked thousands and raped hundreds of women on the streets of Constantinople. The riot destroyed and desecrated Greek businesses, churches, schools, homes even cemeteries. While the pogrom mainly targeted Greeks, Armenians and Jews also faced brutality. While an exact total is unknown, the death total ranges from 13 to 37 and the riot’s damage is estimated anywhere from $24 to $500 million dollars. “Their main main purpose was to eliminate the Greek population,” Mike noted.

Katsantonis was 12 years old and on vacation with his family on the Bosphorus strait Vafiochori (Boyacıköy) when the pogrom began. Earlier in the day, he saw “Cyprus is Turkish” written on the town fountain.

The Greek Cypriots’ struggle for enosis, or the union of Greece and Cyprus, fueled the growing distrust and hatred toward Greeks in Türkiye. Rhetoric from Prime Minister Adnan Menderes incited fears of a massacre of Turkish Cypriots by the Greek Cypriots. From the fall of Constantinople, the strained past of Greece and Türkiye with events such as the Greek genocide and the subsequent population exchanges roughened the relationship between the two nations. It was inevitable that an attack on the Greek minority of Türkiye would occur.

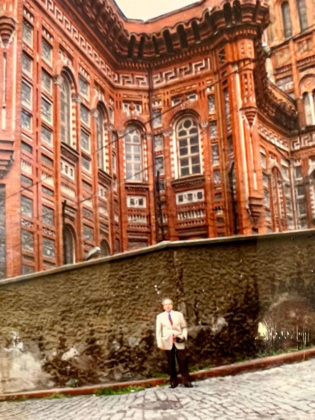

Katsantonis in front of Great School of the Nation in Constantinople

“This is a sequence of interconnected events. There was always discrimination. We had to be careful in order not to offend. This kind of behavior, this kind of fear, was existent throughout for as long as I know,” Katsantonis explained.

He made note of how his father’s Turkish boss behaved in the days leading up to the pogrom. The boss, fearing being targeted as the managers of his wholesale store were Greek and Armenian, took all the money from the store’s safe. “It was well organized. This pogrom was not something that occurred overnight. This was in planning for years,” he said.

When the news broke about the bombing, rioters were transported into the city with lists of Greek homes and businesses. Supplied with axes, crowbars, gasoline and other weapons and tools to decimate and destroy, they wreaked terror on the city and the surrounding area.

A first wave of rioters would mark houses, businesses and churches with paint or throw rocks in windows to signify to the second wave where to loot and destroy. As the mob approached where Katsantonis and his family were staying in Vafiochori, one of his neighbors, a navy officer, told the crowds that Greeks did not live there and to move on.

In Fanari (Fener), someone in the crowd threw a rock through a Turkish neighbor’s window in the neighborhood of the Katsantonis Family home. “He went out and said, ‘Listen, there’s no, there are no Greeks here. They went to the mosque to pray.’ So, because of that, our house was safe,” recalled Katsantonis. Because of the quick thinking of his neighbors, Katsantonis never realized the severity of the pogrom as it was happening.

Katsantonis and his family

While his family escaped harm, his relatives were not so lucky. The pogrom decimated his uncle’s bakery and his aunt’s home was “totally destroyed”. “Imagine all the furniture, all this stuff thrown out of the window,” he explained. Her rugs were cut up completely. His father could not describe the extent of the damage—all he had was the keys to her house with no door.

At a church in Fanari, the mob threw icons out into the street and defecated in the altar. The church caretaker and his family fled through tunnels under the church that have been there since the Byzantine Empire to the Golden Horn.

The violent riot left scars on the Greek Community in Constantinople, however, many could not leave. Between 1955 and 1960, the Greek-speaking population of Istanbul decreased from 65,108 to 49,081. “People in Constantinople, they had their businesses, they had their jobs, we had our schools. They had their livelihoods. It wasn’t a situation where you can just move on. We had to deal with it somehow,” Mike said.

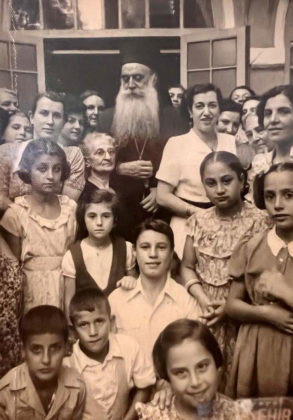

Katsantonis photographed with Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras

Though Katsantonis left Constantinople two years after the pogrom, much of his family remained there. Unfortunately, due to the forced expulsion of the Greek citizenship holding population in Constantinople in 1964, Greeks now make up a tiny fraction of the city’s population today. “Our ancestors were there since the Byzantine Empire. Unfortunately we were at the wrong place,” Katsantonis remarked.

While events of Sept. 6 1955 may have been 68 years ago, its impact on the Greek community and history is crucial to our understanding of how hatred of a minority group can metastasize into violence. “Like the genocides. Like the killings of the Jews. These are things that affect humanity.”

Katsantonis’ experience is a testament to remembering these tragedies so they do not happen again. In 2021, he participated in an event commemorating the pogrom and spoke about his experience to an audience at Zoodohos Peghe church in Bronx, New York. “It’s good that they remember it. They have to remember,” he explained.

Despite him leaving Constantinople when he was 14, he made his way back to his birthplace and revisited what remains of the Greek community. He made sure to visit the Great School of the Nation in Constantinople, which still stands today.

0 comments