ELEVEN DAYS TO THE PROMISED LAND BY DINO PAVLOU

How an immigrant kid became friends with the most famous people in the world

Dino Pavlou was a seventeen-year-old kid from Valtesiniko, Arcadia who came to America in 1952, wearing Mitso the shepherd’s borrowed sheepskin coat, and started working at a pie factory in New Jersey.

“They didn’t pay you by check then,” he remembers. “They put the cash in an envelope. I was getting sixty-five cents an hour, and when I got my first envelope, I locked myself in my room to count it. I counted $46 and something cents for six days of work and then I calculated what it was worth in Greece and, I said, I’m rich!”

He also got drafted into the army during the height of the Korean War.

“They won’t accept you,” said his Uncle George, who brought him to America. “You don’t speak English well.”

Only Pavlou was accepted and he couldn’t wait to join.

“I remember the Allied soldiers when they came to liberate Greece and they were our heroes,” says Pavlou, now 86. “When I got my draft notice I said–now I’m going to be one of them!”

He was barely eighteen, but he soon commanded a tank that won the prize as the best in the battalion, built a baseball field and won a commendation even though he had never seen a game, and while his soldiers groused about army life, he couldn’t wait to go fight the communists.

“They never saw their liberty being taken away from them,” he says of his life back in the village during the Greek civil war. “They never saw their father being executed. They never saw people being killed and dumped down wells. They never saw any of that.”

Unfortunately, or fortunately, the war ended before Pavlou’s unit could be shipped overseas, but he soon made the first of his famous acquaintances.

“There’s a movie company coming down to film some war scenes,” his commander told him one day. “And they can’t have an actor driving a tank. You’re going to be the driver of this movie star.”

The movie star turned out to be Audie Murphy, the most decorated soldier of World War II, who after their scenes were shot for the movie invited Pavlou to look him up in Hollywood. Pavlou did, after he got out of the army, a friendship ensued, the first of many, and the rest is history.

Because after the war Pavlou got into the nightclub business and soon was working at some of the most swinging clubs in New York City in the swinging heyday of the ‘60s and ‘70s, where he got to meet most of the famous stars of the day, and most of the infamous.

“I have so many memories from the past,” says Pavlou. “I have a room which is full of pictures, and all those pictures have stories. So I said to myself let’s put it in writing.”

And he put them down in his new book, Eleven Days To The Promised Land (Newman Springs Publishing), and writing it brought back even more memories.

“Honestly I keep reading my book over and over again because it brings me back to those good, carefree years,” he says. “It was unbelievable.”

After Audie Murphy, he met Frank Sinatra at the legendary Mabel Mercer’s By-Line Room in New York City, where he stuck up for Sinatra during a dispute and Sinatra never forgot it. The next time the singer came into the club and Pavlou addressed him as “Mr. Sinatra,” Sinatra stopped him.

“To my friends, it’s Frank,” he said.

And Sinatra became not just a friend, but when Pavlou’s wife Agnes suffered from cancer and tragically died, Sinatra paid all the medical bills, and Pavlou tried to thank him.

“Lights out, Greek,” Sinatra cut him short.

The singer later did a charity concert in Greece at Pavlou’s suggestion and he serenaded Pavlou’s daughters onstage at one of his concerts.

But when Pavlou became a host for twenty years at the famous Jimmy Weston’s Restaurant and Jazz Club on E. 54th Street—one of the hottest nightspots in the hottest city-he also got to meet everybody else.

There was the man in the deep baritone who asked for a table.

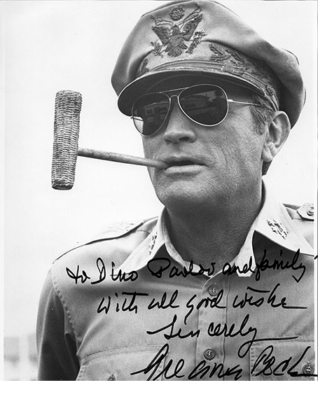

“Will it be long, Dino?” asked Gregory Peck, ever the gentleman, waiting his turn in line.

And Woody Allen playing with his orchestra and keeping his back to the audience—until Dino met him in the bathroom and suggested maybe the club was not his scene.

There was Muhammad Ali sparring with Joe Frazier and also plucking at Howard Cosell’s toupee.

And the Apollo 11 astronauts dropping in for their first public outing since walking on the moon.

“I remember Buzz Aldrin as a very sociable, talkative person,” says Pavlou. “We had a nice, interesting conversation, and at the end, he scribbled down my name and address. A week later I was surprised to receive a package from Mr. Aldrin containing a picture taken on the moon and a golden keychain with an emblem, featuring the Apollo 11 and the American eagle.”

There was Johnny Carson playing the drums with the band, Jackie Kennedy out on the town with Sinatra, and Shirley MacLaine out on the town with writer Pete Hamill.

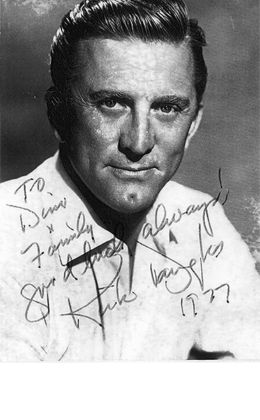

There were Milton Berle, Bob Hope, and Don Rickles doing an impromptu roast, and Kirk Douglas standing up for Phyllis Diller.

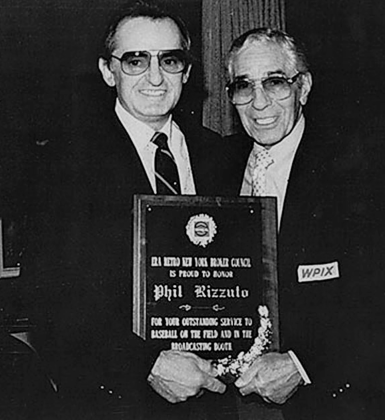

And Roone Arledge telling Pavlou about a new night of football he was planning (“How would you like to see a football game on Monday?”), and George Steinbrenner dropping in with his Yankees all-stars, and Yankees’ All-Star Reggie Jackson answering the phone as Reggie Jackson and taking down reservations.

“Reggie Jackson, who?” Pavlou called one night anonymously and teased him.

And there were the frequent visits of legendary movie star and honorary Greek—Anthony Quinn.

“He made the place his favorite stop, and he was always ready to be the life of the party,” remembers Pavlou. “Anthony and I became close friends, and I still keep in touch with the family to this day. I called him ‘Patrioti.’ When he was in the place, he’d come to me and say, ‘Dino, let’s dance the Zorba dance.’”

Also trying to rub shoulders with the famous were the infamous, like John Gotti, who showed up with henchman Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, and one night bought a couple celebrating their first anniversary a bottle of Dom Perignon.

And wise guys with names like Frankie Chi-Chi, Mike Moose, Jimmy Hot-Hot, Vinnie the Umbrella, and fearsome capo Aniello Dellacroce, who one night asked for cement.

“I’m sorry, I don’t have cement,” Pavlou told him. “What for?”

Dellacroce nodded with a poker face (his usual face) to the ice bowl and the bug floating in the water.

“I got you, didn’t I?” he said with a crocodile smile.

But mostly it was a party atmosphere with a cast of Damon Runyon characters, like Boots, the men’s room attendant, who relied on his tips and once got stiffed by baseball manager Leo Durocher and never stopped talking about it, so it made the rounds of every bar in New York, until Sinatra gave him a tip that was double his monthly salary. Or the punch-drunk limo driver and former boxer who heard a bell once and took off—without his passengers.

And man-mountain wrestler Andre the Giant, who helped Pavlou pull a gag on Pavlou’s cousin Nick, who always bragged about being a tough guy.

So Andre walked over and towered over him.

“Are you making fun of me?” he growled.

“No, no, sir!” said Nick.

Then Pavlou walked over. “Be careful, Andre,” he said. “He says he’s a tough guy.”

And there was a disgraced ex-president who got applause when he got up to leave.

“Is it because I’m leaving?” Richard Nixon asked Pavlou.

“Our customers always applaud for notables, Mr. President,” said Pavlou.

And he still remembers how the ex-president gave him a strange look when he heard the “Mr. President”: “It was like he was looking, searching to find out if I truly meant it. At that moment, I actually felt sorry for him. It was sad seeing the most powerful man in the world, who had fallen so hard, looking for some compassion.”

But perhaps the most enduring memory for Pavlou came on a snowy night during the Christmas holidays when Sinatra walked in with his faithful sidekick, club owner Jilly Rizzo, and he asked if Pavlou had his Chevy parked outside.

“Yes, I do,” said Pavlou.

“Greek, you just got yourself drafted,” said Sinatra. “Let’s go.”

And they got into Pavlou’s five-year-old Chevy Impala and drove uptown in the snow, stopping along the way on Park Avenue so Sinatra could get out and stare at a sky like a winter wonderland.

“Look at this,” he said, “isn’t this marvelous?”

And then they drove to Patsy’s Pizzeria in Harlem, where Sinatra saw the homeless standing outside and shivering and waved them in and treated them all to rounds of pizza, which they gobbled up and forgot about Sinatra.

“You see, Frank,” Jilly teased him, “you aren’t as famous as you think you are.”

“If you were as hungry and cold as they are,” Sinatra said, tears in his eyes, “you wouldn’t recognize me, either.”

And then he put down the money for the free pizzas to keep coming through the holidays, before they drove back downtown mostly in silence.

“Have you ever been cold and hungry?” Sinatra asked.

“I have,” Pavlou said.

And he wanted to capture these memories in a book because he almost doesn’t believe them himself.

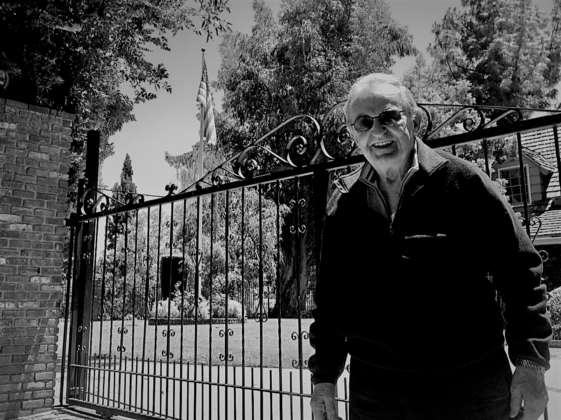

“I often wonder how lucky this kid from a war-torn Greek village was to have the friendship of some of the most famous people in the world,” he says, still marveling at the room in his house where he keeps all the photos of his “friends” and their letters and tributes to him. “I feel fortunate to have called them my friends.”

0 comments