Samos, Where Geography is Destiny

Alexander Billinis

As the Bicentennial of Greece’s War of Independence approaches, in 2021, I will be highlighting various places, people, and events that played a key role in this seminal event. Today, I will focus on an island.

No, not Hydra.

We Hydriots are justifiably proud of our island, its record in the War of Independence, and its breathtaking beauty. No, I am focusing on another island, in the far east of the Aegean, the closest island, in fact, to Asia Minor, where a tiny strait separates the island from the Turkish mainland. This island is Samos.

Like many parts of the Greek world, the Samians rose in revolt in 1821. We sometimes forget that huge swathes of Hellenism participated the Greek Revolution. Crete, Macedonia, Epirus, and even parts of Asia Minor and Cyprus rallied to the revolt, only to be crushed after heroic attempts. The brave Cretans would try another half dozen times before uniting formally with Greece in 1912. The Chiotes lost a huge proportion of their population to fire, axe, and slavery for their efforts, and the Macedonians also fell under the Ottoman sword, to fight another day.

Samos did not fall. Ever.

The flag of the Principality of Samos before uniting with Greece

Despite being a few hundred meters from Asia Minor, far from the established centers for Greek revolt—the Peloponnesus, Central Greece, and the Western Aegean Islands—the Samians by land and sea defended their independence. Even as Ibrahim Pasha ravaged the Peloponnesus only to be evicted by the Great Powers, the Samians, by themselves, held out. Like other Aegean islanders, the Samians had a rich maritime and mercantile tradition, together with a strong love of learning. They would not give up their enlightened ideals of national unification with Greece.

The first Greek State under Kapodistrias included Samos, but in the London Protocol of 1830, which established the boundaries of the Greek Kingdom, Samos was left outside the state. Samians again refused to accept this and a portion of the island emigrated to the Greek Kingdom, but eventually Samos was established as an autonomous principality under a Christian governor.

For nearly eighty years Samos existed—and thrived—as a semi-independent part of the Ottoman Empire. According to the various governing documents, Samos lacked the full trappings of independence, but the island possessed internal autonomy under a Christian governor. Having distinguished themselves with the sword, they did the same with the pen. The island’s sense of self and pride remained high, and they poured their efforts into civic and educational activities, so much that the island’s general level of educational, economic, and cultural standards was far higher than the Ottoman Empire’s or that of the Greek Kingdom. Samian graduates went on to distinguish themselves far and wide, and their men’s and women’s schools attracted the best teachers from Greece.

A relatively small island hideously exposed to Turkish revenge, Samos remained nominally quiescent even as Aegean Islands like Crete, further from the centers of Ottoman power and with massive, guerilla-laden peaks, continued revolting against Ottoman rule. However, Samos was not idle, building a progressive mini-Greece. The first iteration of Samian autonomy, until 1849, was very regressive, with high taxes on a population reduced by emigration to Greece and elsewhere, but the Samians pushed for—and obtained—better governance, organizing their small island with a progressive ethos the Greek Kingdom could never achieve. Public works, economic growth and diversification were hallmarks of this tiny principality. A good half dozen newspapers point to a literate and an intellectually—as well as commercially—inclined populace. The elegant public architecture of today is testimony to their efforts and taste.

In 1912, as the Greek navy inflicted shattering defeats on the Ottoman navy, the various eastern Aegean Islands were mopped up by amphibious landings. Waiting for a Greek landing, the Samians’ leader, Themistocles Sophoulis (later to become Prime Minster of Greece) is said to have cabled Athens, “Do you want us or not?”

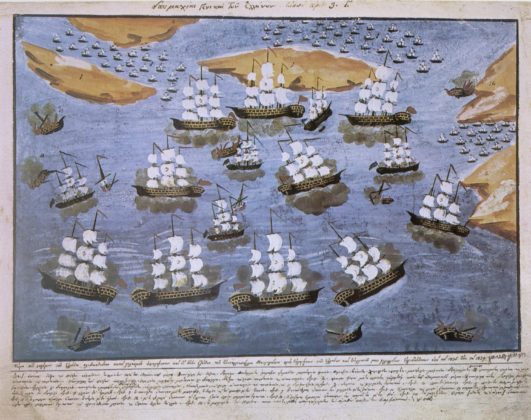

The Battle of Samos. Painting done by Zographos at Makriyannis’ direction

Samos’ autonomous status ended with its union with the Greek motherland after the Balkan Wars, and though the Samians rejoiced at joining with their Greek brethren, they could not help but feeling a sense of loss. They were governed from a distant, statist Athens, with a governance culture far less progressive than that of the late Samian Principality. Further, and most particularly with the Asia Minor Disaster in 1922, Samos was effectively cut off from the economy of Asia Minor, of which it heretofore had been a vibrant part.

Notwithstanding, the Samians were patriotic and progressive Greeks, like other Greeks proud of their regional origins and history. They became the akrites, the frontier guardians, of a Greece locked in perpetual Cold War with Turkey, far closer to Samos than indifferent Athens. The Samians nonetheless persisted, though they must have asked themselves the same blunt question that Sophoulis had asked Athens—“Do you want us or not?”

Samos is a rich island, blessed with a fertile soil and beautiful climate, together with inhabitants who love their island. In spite of a degree of official indifference and the isolation of a frontier zone, Samos retained its charm and a relative prosperity, together a manageable flow of visitors who appreciated its elegant beauty, a far cry from the kitsch of Mykonos and other islands.

Samos is a case study in geography as destiny, caught between two continents, and the cold-and-hot wars of Greeks and Turks, the Samians have always acted honorably, defending their identity and their island notwithstanding the indifference of Athens. In the past decade, the Samians, like all akrites (border) Greeks, took in refugees from Syria with a hospitality Greeks are noted for, and with a view to their own recent pasts—often personal pasts—as refugees. From helping those in need the Samians now contend with a wave of migrants rather than refugees, literally dumped on the island by Turkey, which is now overwhelming the beautiful island that has long stood guard for Hellenism. Geography (partially) insulates the rest of Europe, and indeed parts of Greece, but not the Samians. Perhaps they should once again ask the question in 2020 that Sophoulis asked in 1912.

Failure to answer this in the affirmative, and to act on it, will indict all Greeks . . . .

0 comments