War and Remembrance

One family’s war memories

My grandmother in Chios, Greece had a big lacquered cabinet (with a pattern of flowers) and on top of it, incongruously, stood the housing of two gleaming-gold cannon shells: with wheat stalks in them for decoration.

I was a kid growing up in Chios with my grandparents and I would occasionally stare up at the cannon shells when my mother put me to sleep for my afternoon nap. They were beautiful, I thought, and I wished that when I grew up I would go to war and get my own cannon shells.

They had been brought back from the Greek civil war by my father, who had served as an officer at the front for five years—the best years of his life—his early twenties, and who was among the few officers who had returned.

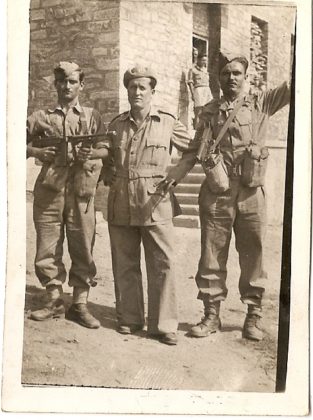

All I knew was that my father had been in “mahi” and I imagined that “mahi” was something that I saw in my Greek mythology books (with the serrated edges), which showed ancient Greek warriors like Achilles and Hercules. I never saw the heroes of Greece’s modern conflicts, until, one day, in a rusted metal footlocker with a rusted clasp, I saw this murky photograph of a soldier from a distant conflict wearing chaps over his boots and a gun belt and straps over his dark shirt and a rifle slung high over his chest like he was facing off against an enemy. He had no glasses on and a thick mustache like a brush—but I couldn’t miss that head cocked back, those eyes squinting, and that chin set stubbornly—it was my grandfather in another life.

All I knew was that my father had been in “mahi” and I imagined that “mahi” was something that I saw in my Greek mythology books (with the serrated edges), which showed ancient Greek warriors like Achilles and Hercules. I never saw the heroes of Greece’s modern conflicts, until, one day, in a rusted metal footlocker with a rusted clasp, I saw this murky photograph of a soldier from a distant conflict wearing chaps over his boots and a gun belt and straps over his dark shirt and a rifle slung high over his chest like he was facing off against an enemy. He had no glasses on and a thick mustache like a brush—but I couldn’t miss that head cocked back, those eyes squinting, and that chin set stubbornly—it was my grandfather in another life.

My papou, that little man stooped over, in the sun hat, and the plaid shirt buttoned all the way up to his Adam’s apple when he worked in the fields, that little man was the mighty warrior in the old photograph.

I asked him about it, and he patted his hands and looked embarrassed, or he looked away because the subject was too complicated to encapsulate.

“That was a long time ago,” he said.

“How long?” I said.

He looked away again.

“Long ago,” he said.

But I got the story in other ways: on the nights when our neighbors in Kofinas came over for their evening “vengera” and they got my grandfather to talk history (he worshipped Plastiras, the incorruptible George Washington of modern Greece, to my grandfather) and in that recitation of history, while the moths flew around the lightbulb at night on the “verandah,” my grandfather would also tell his story.

How he was a farm boy up in the village mountain of Kourounia. How a draft was called. How he and others took pack mules and rode to Chios town and got housed in makeshift barracks and ate their first military rations (beans with pork fat and worms).

And then they marched in wooly uniforms and oversize backpacks that now carried their whole life into steamers with huge rivets and funnels like the Titanic into the bowels of the ship where the engines drummed and the seas splashed the sides and made the hull sweat and the seawater seep in and make their hold smell like “sardeles.”

“And when we got to the front, we pushed into Macedonia,” said my papou, patting his hands, staring at a misty horizon, his chin stuck out again just like in the photograph. “We didn’t stop for anything.”

He was at war long enough to ruin his health for life (he wore sweaters in the swelter of the day) and he talked about his battlefield experiences only in inspired moments, but he was very content that he had done his part for Greece.

Up in Kourounia, my other grandfather Dimitrios, also had a photograph of himself in uniform wearing his spats and his mustache and his jacket buttoned all the way up to the collar over the bureau in the bedroom (the house only had two rooms) right next to his wedding picture—which I’m sure my grandmother only tolerated.

And when he went down to the “kafeneio” of the village and had a few “soumes” and “krasia” with the other men, his gold teeth would flash in the light of the gas lamps as he told his war stories, and they told theirs, about the miles they marched in the wars, and the mountains they crossed, and the icy streams they forded.

“The water came up to here!” my grandfather would say heatedly. “It would come right up to here! And when the water snakes came after us we would just throw them aside! And the bullets we caught with our teeth!”

They would laugh a little, and drink their souma, and water it less as the night wore on and the tales got taller.

But the genuine war hero in the family was my father, and he was a fabulous storyteller, so the stories he told were like an epic of modern Greece.

Of him as a university student in Thessaloniki being rounded up by the Germans and put in a concentration camp for dangerous intellectuals.

How he escaped by speaking German (what he had learned in school) and taking a “kaiki” loaded to the gunwales with refugees like him that, miraculously, made it from Thessaloniki to Chios.

How he survived “Katohi” in Chios up in the mountains and like everybody else lived on dandelions, beans, olives and “spouryites” (sparrows) shot down with homemade slingshots.

How when the “peace” came he was drafted into the Nationalist Army in the Greek civil war and at the ripe age of twenty-two was enlisted as an officer on the front facing the communists of Yugoslavia.

There was the time the train his troops were riding was ambushed as it reached a tunnel and got stranded in the tunnel while enemy troops attacked it from both ends. And how he coordinated counterattacks and got his troops out and the villagers nearby gave them a parade for their heroics—my father leading the parade and saluting British-style open-palmed—one of my favorite photos of him—and later my father getting pinned with all his medals for bravery.

There was the haunting story he told of a widow in one village who had only a son left after the years of fighting and when a colonel drove with his entourage through the village in an armored detail how a flash of sun made the colonel’s armed detachment think the son was pointing a rifle at them and shot him dead—the last male in her household.

There was the story of my father’s master sergeant, named Dimitris Touloumides, a giant of a man, who had one baby daughter, as my father had one baby daughter, and how they spent their nights talking under the stars at their mountain outpost about the fateful day when the war would end and they could join their wives and children and go on with their lives: the eternal lament of all fighting men. How there was a skirmish that night at the foot of the mountain and Touloumides was due to go on leave for the first time the next morning, but he volunteered to lead a reconnaissance patrol.

“I’ll take it,” said my father.

“What’s the difference?” said Touloumides. “If my time is up, my time is up.”

My father couldn’t convince him to stay, Touloumides led the patrol, and he was killed that night in a skirmish in a wheat field: my father and his unit found the bodies the next morning, with Touloumides locked in a death grip with an equally-young and unfortunate foe.

“Why don’t you write about that?” I asked my father over the years.

And he always said he would, and tried several times: he left fragments behind in his spidery script, some on onion paper, in boxes that I keep in my basement.

But they are only fragments, like the flash of the gunfire he witnessed all those nights on the front up in the mountains, where the fate of the whole world, and certainly Greece, seemed to rest on the shoulders of mountain boys like my papoudes and my father, and their courage secured a future for the rest of us.

0 comments