What do we really want on the Macedonian Issue?

by Endy Zemenides

When Phillip II assumed the throne of Macedonia, his kingdom faced existential threats. He had just taken over a kingdom whose predecessor fell in battle; the same battle cost Macedonia most of its army. Youth, inexperience, a weak military and threats on every border. To label the situation that Phillip II inherited “not promising” would be an understatement.

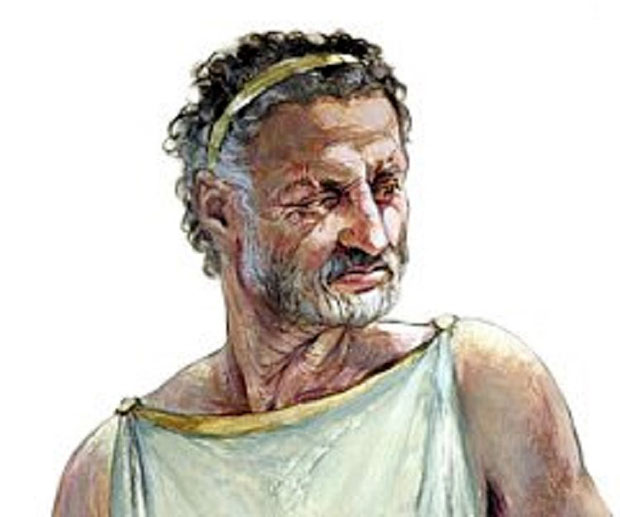

Needing time to rebuild his army, Phillip resorted to treaties, bribery and a marriage of alliance in order to quash the threats to Macedonia. It was Phillip’s diplomacy – not his phalanx – that bought time for Macedonia’s rise, for Alexander the Great to come on the scene, and for the Hellenic legacy of Macedonia to make its way through time down to us. Nearly 2,400 years later, the northern region of Greece that is Phillip’s Macedonia is in need of the same statesmanship to secure its future and perhaps regain some level of glory or significance. Yet the debate over the Prespa Agreement is marked more by the demagoguery of Phillip’s archnemesis Demosthenes than by Phillip’s diplomacy.

Philip II of Macedon

Rhetoric that includes words like “traitor”, “surrender”, or exclamations like “we gave away everything” has become the norm when the Prespa Agreement comes up. (It is interesting to note that the detractors of the Prespa Agreement in FYROM use the same language). But this rhetoric, as well as the overwhelming number of charlatans that employ it, do little to safeguard either Hellenic national interests or the Hellenic cultural legacy.

The time for a dialogue over what the end game is for Hellenes on the Macedonian “issue” is long past due. The problem has been transformed from a national issue into a domestic political issue – both within Greece and in the diaspora community. The Prespa Agreement may indeed be dead (or at least on life support), but everyone weighing in on the future of this issue needs to have answers to some fundamental questions if we are to avoid this becoming yet another frozen conflict that Greece has to deal with for decades.

- What do we all agree on?

Despite the bitter nature of the debate over Prespa, there is a consensus over the Hellenic legacy of ancient Macedonia, Phillip and Alexander. Yes, it is offensive to witness Greece’s neighbor and fanatical parts of its diaspora lay claim to our history. But go to Classics Departments all over the world, to museums, to history books. Even decades of their propaganda has had no serious effect. NONE. Our outrage would be better directed at the lack of effort within the Hellenic world to better celebrate and promote the Hellenic legacy of Macedonia. The forums are certainly there: museum exhibitions – both permanent and temporary; scholarship in history and the classics that have decisively settled the issue. These tools can be used by us all to accomplish the goals of securing our history and heritage.

We also all agree that any resolution must safeguard Greece’s territorial sovereignty and promote regional stability, which leads us to. . .

- Who is OK with the status quo?

Detractors of the Prespa Agreement have raised the prospect of a better deal for Hellenic interests. Noone explains how they are going to arrive at such “better deals” — which range from the impossible (a name that doesn’t include the word “Macedonia” in any way), to the increasingly unlikely (if a solution that allowed for a “Macedonian” language and identity — albeit unrelated to ancient Greece or the territory of Greece — could not get widespread support throughout FYROM, how will a framework that takes this out get approved). Even this week’s talk of a Plan B coming from the Defense Minister seems like an attempt to kick the can down the road.

In the meantime, you will have a country that still claims a “Macedonian” identity and language, and on top of that has a constitutional name of “Republic of Macedonia”, bilateral relations with most of the world under that same name, and official educational policy that makes claims on Hellenic history and even territory.

One would assume that it would be easy to establish consensus that this status quo is annoying/offensive in the least. It also allows tangible threats to gather on Greece’s northern border. Skopje’s past alliances with Turkey and Russia are one threat. Skopje’s need for alternatives to ports and other transportation in Greece has allowed for a Balkan infrastructure that would be exclusive of Greece, cutting the country off from natural trading partners. Assuming the allure of NATO and EU membership will permanently be a source of leverage over Skopje ignores trends in the region. If a future VMRO government decides to transform FYROM into a Russia client, the prospects for a diplomatic solution may disappear altogether.

Whatever the fate of the Prespa Agreement, it is time for the people of Greece and the Hellenic diaspora really consider what issues they want solved, and they best get solved. There is no sense in reaching a solution merely for the sake of reaching a solution, but it is also unwise to rush into a frozen conflict without fully thinking the consequences through. Right now too many stakeholders in Greece are hoping the Agreement fails in Skopje and thus takes them off the hook. That is not the type of diplomacy that Phillip used to save Macedonia.

0 comments