- FOKION AVGERINOS – DR. IKE: Athletic Director, Youth Mentor, and Healer

- American Hellenic Institute’s Golden Jubilee Celebration

- Leadership 100 Concludes 33rd Annual Conference in Naples, Florida

- Louie Psihoyos latest doc-series shocks the medical community The Oscar–winning director talks to NEO

- Meet Sam Vartholomeos: Greek-American actor

From the Shores of the Aegean to the Edge of the Pacific

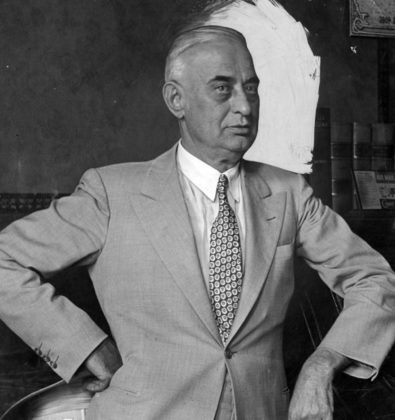

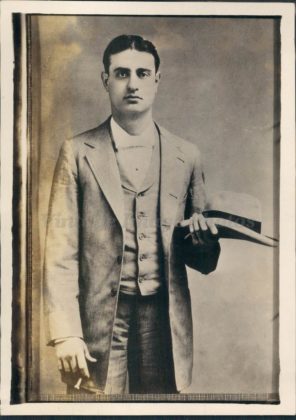

A tribute to Alexander Pantages (1864/75–1936)

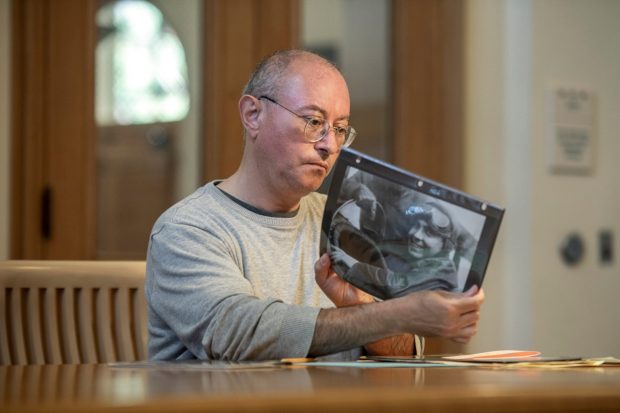

By Ilias Chrissochoidis, Ph.D.

Few Greek-American stories can match the roller coaster life of Alexander Pantages, a penniless boy from the Aegean who built a theatrical empire in the American West before retiring in public humiliation.

As with many first-generation immigrants, Pantages’ early life is shrouded in mist. He was told he had been born “on one of the Dodecanese Islands, off the coast of Greece” around 1864 but his first memories were from Cairo. At age nine he run away from his father and boarded a French ship. Two years later he ended up in Panama where he worked in the construction of its canal before an outbreak of malaria would force him to move to California. By 1896 Pantages had settled in San Francisco and owned a restaurant at 121 Fifth Street. In December of that year, he was arrested for smuggling opium, but the charges were dropped after he had established that he was training for a prize fight during the night of the alleged crime.

Joining the Yukon Gold Rush in 1898, Pantages moved to Dawson City where he met and eventually partnered with dancer “Klondike Kate” Rockwell in theatrical enterprises. Later he would claim that his first theater was making $3000 a day for four years, but the half million dollars he made was finally lost in bad deals. With the remaining $4000, he moved to Seattle and bought the Crystal Theatre in 1903. An illiterate man who spoke broken English with a thick accent, Pantages was ridiculed and bitterly fought against by the city’s theatrical establishment. His inability to book great attractions forced him to branch out opening theatres in Spokane, Denver, and Davenport. Several double crossings by his partners led him to pursue a fiercely independent career. (“I have no partners except the wife and children … I want to direct everything myself. I want to decide everything myself. If I stop, I am lost. It is my way.”)

Hard work, an exceptional memory, and personal involvement in all aspects of his business brought Pantages quick success and led to an Alexandrian campaign of theater house acquisitions and construction. (“I shall not be happy till I own a chain of houses from the Atlantic to the Pacific—from the Tobaggans to the Everglades.”) During the 1910s his theater circuit dominated the American West and by 1918 he was “the sole owner of $5 million [$94 million in 2022] worth of theaters.”

The rapid growth of the film industry during the 1920s put pressure on his vaudeville empire and eventually led to its demise in 1929. In mid-April of that year, he reached a tentative agreement with Joseph Kennedy to sell his entire chain of 15 theaters and theatrical real estate to the Radio-Keith-Orpheum corporation (RKO) for $14 million. Difficulties rose, however, and he finally sold (July 25) only six theaters to RKO for $4.5–5 million and to transfer, on August 7, two theatres, including the flagship on 7th and Hill Road in Los Angeles, to Warner Brothers. Reported at the time as cash payments, his family later claimed that they were paid in stocks of the respective companies, which were soon to be depreciated. Pantages kept to himself only the crown jewel of his empire, the Hollywood Pantages, which would open on June 4, 1930.

The stock market crash of 1929 found Pantages fighting legal battles that ruined his health and claimed much of his fortune. On June 16, his wife Lois caused a car accident that left a man dead and several others injured. This was followed by his famous arrest on August 9, on charges of attempted rape against 17-year old dancer Eunice Pringle during a meeting in his office. Bad timing (the weeks preceding Black Monday), a foolish attempt on his part to influence witnesses, a hostile District Attorney, a severe judge, and public outcry fueled by William Hearst’s tabloids, led to a prison sentence of one-to-fifty years. Pantages would remain incarcerated in San Quentin until June 1930, when in the aftermath of several heart attacks and hospitalization, he was released on a $100,000 bond. He finally was granted retrial two years later. This time his brilliant lawyer Jerry Giesler was able to dismiss Pringle’s account as improbable, to question her moral character and to suggest ulterior motives in her accusations. Although finally acquitted, Pantages was left with legal and medical bills worth $252,095.

Pantages always maintained that Pringle had framed him, and later commentators speculated that Joseph Kennedy had bribed her to compromise the Greek magnate and acquire his theaters at half price. Rumors about Pringle’s confiding her “secret” before dying under suspicious circumstances are based on the collation of her uncle’s suicide (November 25, 1929) and her disappearance from the public eye (she actually died in 1996). As she admitted in the retrial, she had been pursuing Pantages to book her dance number since May 1929: he could easily have seduced her then (and why would one rape a dance girl that one had refused employment three times?). It is almost certain that Pringle was after money, for the fatal meeting with him came only days after Pantages was reported flushed with millions from the sale of his theaters; even after his conviction and first heart attack she would still attack him with a $1,000,000 damage lawsuit. The absence of evidence against Kennedy is not proof that he may not have taken advantage of the scandal, especially since the Los Angeles Examiner, owned by his friend Hearst, was the forerunner of attacks against Pantages. In hindsight, it could be said that Pantages was a casualty of the brutal corporate wars fought in the motion picture industry during the late 1920s.

Pantages ended his retirement on November 21, 1935, when he announced plans for expanding his two-theatre company: “The depression is over. The court tragedy is passed and Alexander Pantages is back in the show business—100 per cent. I tried oil, mining and other investments, but my business is the theater and it’s great to be back.” His dream was not to come true this time. He died in his sleep from heart failure on February 17, 1936. He was survived by his wife Lois, his two sons Rodney and Lloyd, his daughter Carmen and step-daughter Dixie. His estate was reported to be a mere $5,026. Among Hollywood notables attending his funeral were the Skouras brothers, who would succeed him on the Greek throne of Hollywood.

Further reading:

- Theodore Saloutos, “Alexander Pantages: Theater Magnate of the West,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 57(4) (October 1966), 137–147.

- Taso G. Lagos, “Poor Greek to ‘Scandalous’ Hollywood Mogul: Alexander Pantages and the Anti-Immigrant Narratives of William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner,” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 30(1) (May 2012), 45–74.

Ilias Chrissochoidis (https://web.stanford.edu/~ichriss/) is a Stanford-based research historian, author, and composer. He has pioneered research on Skouras’ life and humanitarian achievements, and has made numerous archival discoveries on modern Greek history.

0 comments