- FOKION AVGERINOS – DR. IKE: Athletic Director, Youth Mentor, and Healer

- American Hellenic Institute’s Golden Jubilee Celebration

- Leadership 100 Concludes 33rd Annual Conference in Naples, Florida

- Louie Psihoyos latest doc-series shocks the medical community The Oscar–winning director talks to NEO

- Meet Sam Vartholomeos: Greek-American actor

“Where Is the World?” Daphne Matziaraki’s 4.1 MILES: A Response to the Refugee Crisis

by Chris Salboudis

Captain Kyriakos Papadopoulos, PHOTO: YANNA KATSAGEORGI

Sitting in the cozy screening room of the New York Times building in the heart of Manhattan with scholars as well as film and media professionals, Nicholas Kristof, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning Human Rights columnist for The New York Times, introduces Daphne Matziaraki’s Oscar-nominated documentary film, 4.1 Miles. Mr. Kristof comments briefly on the historical challenges of refugee communities as witnessed in WWII, and includes a personal reference to the difficulties his own father faced as an Eastern European refugee admitted to America in a time of Cold War. Had it not been for that single action of acceptance, we may have been denied one of the greatest Human Rights journalists of the present day, which brings us to the point of 4.1 Miles and the thought that our actions in these stressful times are what count. “We as a country refuse to accept [refugees]… and now we have this wave of about 60 million people worldwide, some of the world’s most vulnerable people, and Lesbos, featured in this film, 4.1 Miles, is at the epicenter of that. Traditionally the New York Times tells stories to get people’s attention with ink on dead trees, and now we recognize that storytelling has to evolve in all kinds of forms. We still are fundamentally in the same business that Homer was in, but we know that the platforms vary. This film is very much a part of our broader referent to tell this story of refugees, to humanize the issue… to educate but also to galvanize people and help build a response.… Images in film often move people in ways that words don’t.”

The room goes dark and within moments the viewer’s heart catches at the sight of refugees who were set off onto the sea by human traffickers without direction. Sighted by the crew manning a small Coast Guard boat along the shores of Lesbos the desperately bewildered refugees are awkwardly hauled onto the boat by the brave crew. The film begins in medias res as the Captain of the ship, Kyriakos Papadopoulos, spots and rescues yet another band of refugees. He and his crew of 10 work quickly to save refugees of all ages from drowning as a result of trying to cross cold choppy waters in flimsy rubber rafts.

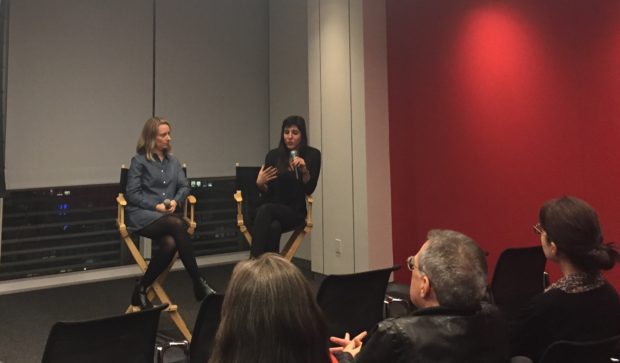

Director Daphne Matziaraki and Executive Producer Kathleen Lingo

Children are weeping, chilled to the bone and understandably traumatized by this experience. At one point Captain Kyriakos orders Ms. Matziaraki to “Put down the camera and hold this baby!” She complies without hesitation. Can there ever be hesitation in the face of clear human need?

Several are treated for hypothermia and pulmonary edema. Some are immediately revived by the Coast Guard with basic CPR as soon as they are safely on the ship while others need emergency care as soon as they reach the shore. Two ambulances and their EMS crews await at the port to help. Countless men women and children of all ages are rapidly treated and covered in foil blankets without a question, without a word. Medicine, dry clothing and blankets – anything warm that’s available – is offered in the truly selfless spirit of Philotimo, and despite the Greek community’s own financial crisis. “I can’t reassure them,” says Captain Kyriakos, “it’s impossible…. When I look in their eyes I see their memories of war.”

Nicholas Kristof, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning Human Rights columnist for The New York Times, introduces Daphne Matziaraki’s Oscar-nominated documentary film

At night, villagers come to watch and help. Inside his cabin, Captain Kyriakos compiles a journal of the sick and wounded treated, praying that there was no one missing from this group. The film concludes with a notation that from 2015 to 2016 approximately 1000 drowned in the attempt to cross into Greece. While Ms. Matziaraki and her team were only in Lesbos and on that boat for a three weeks, the film truly captures the essence of the crew’s bravery and the island’s hospitality in this critical time of crisis.

The question in the minds of many viewers? How can a small island with so few resources unquestioningly provide emergency care to so many? The feat seems epic. It is epic, especially in a time where there are so many plans to build walls, when so many doors and hearts seem to be closing. Ms. Matziaraki addresses related questions moderated by her Executive Producer Ms. Kathleen Lingo of The New York Times in an open interview following the NYC screening of her short-but-poignant documentary.

Ms. Matziaraki states that 4.1 Miles is not specifically a call to action for its international viewers, and yet the process of documenting the crisis and revealing its true impact to viewers is a commitment to raising global awareness. “The film is meant to bridge the gap between these two worlds, between our comfort zones and the real world… it just seems so detached.” In her interview she explains that she was inspired by her own initial response to news received at the peak of the refugee crisis. “I really couldn’t help feeling detached from the whole issue and very distanced. I found that very surprising because I am from Greece and thought I would be more connected to it all…. You know when big news happens we read about it and we feel sympathy or empathy for it, but then we go on with our everyday worlds and that bothered me a lot.“

When asked “Why Lesbos?” Ms. Matziaraki explains that the small island was at the center of the activity because of the direction the traffickers were sending the refugees. “I was reading that it is only 4.1 miles between Lesbos and the Turkish coast, that many people were drowning, and the Greek Coast Guard was at the forefront of this all, which I found incredibly interesting because I knew that the Coast Guard is not actually trained to do any of this. Their job involved routine border patrol around the islands, which is a very easy job because Greece is a peaceful country. So they were just going around the island, checking that everything is okay, and then going home and having a very sweet, easy life on a beautiful island. So I found that these people are, you know, not equipped; their boats don’t have enough thermal covers, they don’t have the necessary equipment nor any kind of way to lift these people out of their boat, so I couldn’t stop thinking about these people and how their lives have changed and how they are responding…. They’re not doctors, they’re not volunteers…. They’re people like you or me who have nothing to do with this crisis and yet now they are somehow caught in the middle of this and they have to respond. So these two worlds I was describing are suddenly colliding with each other in a bizarre and tragic way. So I thought I have to get on that boat.” Ms. Matziaraki states that Captain Kyriakos is one of three Coast Guard Captains caught up in this unexpected “tour of duty” to help save the countless refugees crossing into Greece.

Ms. Lingo points out that the filming team for this project was very small and asks Ms. Matziaraki how people responded to having film crew on site to document what was happening to them, how the team processed the experience of being there, and what ethical and emotional challenges they faced. Ms. Matziaraki replies that she had read up extensively on the issues and the situation in Lesbos before arriving to the small island and had thought herself prepared, only to find, upon arriving, that the reality was completely different from the expectation. “The scale was massive. I have never been to war…. I have never seen people coming from war, and that was the most striking thing for me. You could really tell the trauma in these people’s eyes… so scared and in such a state of emergency…. It really changed me.”

“When I arrived and I saw the reality of the situation, that it was only four Coast Guard boats, two ambulances, one helicopter and nobody else – one hospital all the way on the other side of the island, completely overwhelmed, and very few volunteers coming from all over the world to help – it was so different from anything I had seen in the news coverage. So I thought, ‘Ok I will tell this story exactly the way it is.’” Her initial concern was to stay out of the way of the Captain and his crew since she is not trained in CPR or emergency care. “But reality is always different, and in that first scene when the Captain told me, ‘Put the camera down and hold this baby!’ there was no second thought crossing my mind. The ultimate human thing to do is this. I didn’t think, ‘Oh no, I’m a Filmmaker, I’m not trained to do this kind of thing!’” She says everyone helping was working from a natural human reflex to help another person in need.

Ms. Lingo also points to the more specific idea that the Greek community that is already in its own state of financial crisis, is able to help the refugees, to which Ms. Matziaraki adds that on the evening of October 28th 2015 that her crew was filming the villagers who were coming down to the shores for their face-to-face update of the crisis; that night, one of those being treated had died and a villager shouted to the crew. “We’re glad the cameras are showing what’s happening to the world because we can’t be going through this alone.” Ms. Matziaraki says, “This is how the people on the island really feel. When I was there I remember looking around and thinking, ‘Where are the helicopters? Where is the police? Where are the ambulances? Where is the world? Where is everybody to help?’… The refugees rely on smugglers who tell them, ‘Take the boat. Greece is straight ahead. Just go.’ And then the Greeks are there, completely unprepared and bankrupt, and seeing thousands of people coming. People are overwhelmed. When there is no infrastructure, people get angry. But when I was there I saw people go out of their way to help. When people are dying on your doorstep there is no saying, ‘Oh no… they are the refugees we don’t want to help them. We don’t have the infrastructure.’ You help. There is no other way. It’s the visceral responsibility that the Captain is in. He feels this huge responsibility to respond.”

In a recent Skype interview with Captain Kyriakos the team of 4.1 Miles is informed that there is currently a type of agreement between Turkey and Greece with regard to refugees, however there are many refugees who still come in this way and the Captain and his team, along with the villagers of Lesbos, are still dealing with this situation. There are currently refugee camps set up in an attempt to accommodate those in need, but resources are limited.

Several members of the audience took the opportunity of the film screening to congratulate Ms. Matziaraki for her diligence and skill in documenting the refugee crisis in a remarkably telling light. It is the perfect piece to feature in a Global Studies or Philosophy classroom – as this author has – to help today’s youth and scholars understand the full impact of the refugee crisis and it’s impact on Greece. 4.1 Miles is a phenomenal call to heart, a call to reason, a call to extend our hands in friendship and basic humanitarian brotherhood.

Director Daphne Matziaraki, a documentary filmmaker born and raised in Athens, Greece, holds a Masters in International Relations from the University of Bristol in England as well as a Masters in Documentary Film from UC Berkley and currently resides in San Francisco, California. Executive Producer Kathleen Lingo is Commissioning Editor of Opinion Video and Executive Producer of The New York Times’ award-winning Op-Doc series, which has published over 200 short interactive documentaries. For more about the team behind 4.1 Miles, visit https://www.daphnematziaraki.com/bio.

0 comments