- “La Parisienne” Goes to the Opera: Maria Callas as Priestess

- Over 40 US Policymakers Commemorate the 50th Dark Anniversary of the Turkish invasion in Cyprus at 39th Annual PSEKA Conference

- Remembering The Turkish Invasion of Cyprus and The Fight to Flee with Famagusta Native and Founder of Aktina FM Elena Maroulleti

- Marc Chagall And Greece: A Love Story

- $17 Million AHEPA Gift Will Open Doors For A Generation Of Students

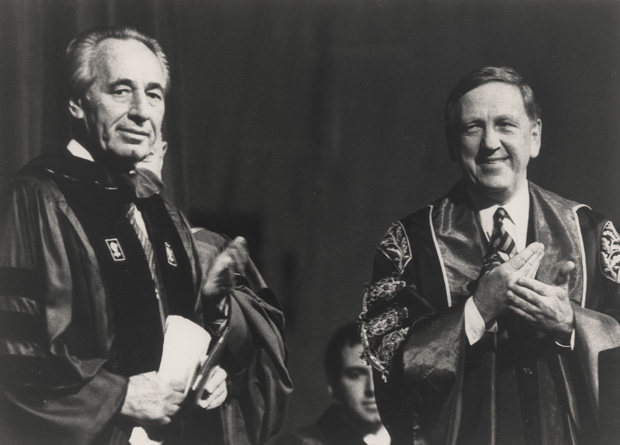

John Brademas: A lifetime of public and private service

John Brademas (1927-2016) In Memoriam

A reprint of NEO’s cover story, May 2007

John Brademas is still in a hurry, even more so now.

He just celebrated his 80th birthday, but as he leads the way through the King Juan Carlos I Center at New York University, which houses his office (he is president emeritus of the university), he carries with him a folder with papers and lists of the things he has to do—in addition to the card he carries in his pocket of his daily to-do list.

And while he leads the way up the stairs to an empty conference room, he gives a brief description of how the Center came about (Brademas became interested in Spanish culture when he was just a boy back in South Bend, Indiana after he read a book on the Maya); how he convinced the sponsors on the wall to give their million-dollar donations (he was a prodigious fundraiser in his tenure); and while the conference room has an air of serenity (it has glass doors overlooking a garden and a portrait of the King) John Brademas is still ticking off projects, remembrances and facts as we sit at the table and he discusses the three-quarters-century of history he has witnessed and three-quarters-century of history he has helped create.

“If I am the first native-born American of Greek origin elected to Congress, to the House, Paul Sarbanes is the first Greek American elected to the Senate, and we’re very close friends,” he declaims, with a characteristic click of the jaw, his voice reverberating in the empty room. He mentions that because among other things on his to-do-list (the longer one in the folder) is a planned trip to Cyprus later that summer with Sarbanes, where both men will accept official honors from the Cyprus government.

That’s after a preliminary junket to Greece his cousin Anna has booked for him “to attend meetings of the symposium of the Academy of Athens, of which I am a corresponding member.” He will give several lectures at American Hellenic University and European Center of Public Law (“And I’m not sure where else she has me scheduled”). “After that,” he reels off, “I should be in Salamanca in June for a meeting of the U.S.-Spain council, and I was supposed to have been in Tokyo this month because I’m on the US-Japan foundation.”

The night before he was at the Central Park Boathouse for a reception, and he was planning to attend a reception that night at Hunter College “and the person who invited me is the son of a fellow Rhodes Scholar, George Steiner, with whom I went to Oxford. And his son is the dean of Education at Hunter College and he’s going to be introducing a woman from the Harvard School of Education, and as a Harvard overseer, I was chairman of the Overseer Committee, so it’s a kind of a sense of obligation that I turn up.” That Friday he also has a symposium on the Spanish civil war “and I will talk about communists and anarchists. And then I’m going—“ he shuffles through his calendar “—to lunch tomorrow with a famous scholar of the Spanish civil war, Gabriel Jackson. And I’m going to a dinner with some Greek friends of mine–anyway, I could go on and on. And then I take off for Greece—“ he resumes “—and I have lunch with Lord Patten, who is the former governor general of Hong Kong and is the chancellor of Oxford University.”

Squeezed in was a birthday party in his honor at NYU, where they showed a film shot by CBS when he was first elected called Mr. Brademas Goes to Washington. “And they had pictures of my mother and father and me in South Bend saying goodbye. And then my arriving in Washington, and of my talking with President Truman. I attended a breakfast in the old Supreme Court chamber for the newly-elected Democratic members of the House of Representatives. Speaker Rayburn was our host, and among the special guests was former president Harry Truman. So I went up to him and introduced myself and I said, Mr. President, I’m being followed around by a cameraman who’s doing a film for young people, which I thought would touch Mr. Truman, which it did, on how a new member gets into the system, and I’d be very grateful, Mr. President, if you’d step outside and let me ask your advice for a freshman member of Congress. And Truman said, always vote with the leadership. So we stepped outside, put the microphones on, and I said with great dignity, Mr. President, you’ve been a great President of our country, what advice would you have for a freshman member of Congress? And without missing a beat, President Truman said, always vote in the public interest.”

Which reminds him of a story about his birthday and LBJ. “Phone rings. Mr. Brademas? Yes. This is the White House, just a minute, here’s the president. That familiar voice comes on. Johnny? The only person who I ever let call me Johnny. I see it’s your birthday. If I’d have thought about it, I would have spent 40 cents on you. I know that young fellows like you could be out making a lot of money, but you prefer to serve your country and I want you to know I appreciate it.” Brademas pauses, just for a second, to smile. “It’s a pretty nice birthday present.”

And a fitting one (caught on tape by Johnson and now characteristically among the Brademas archives, of which there are 500 boxes just of his congressional papers alone) for a man who may be among the most notable men of public and private service in American history.

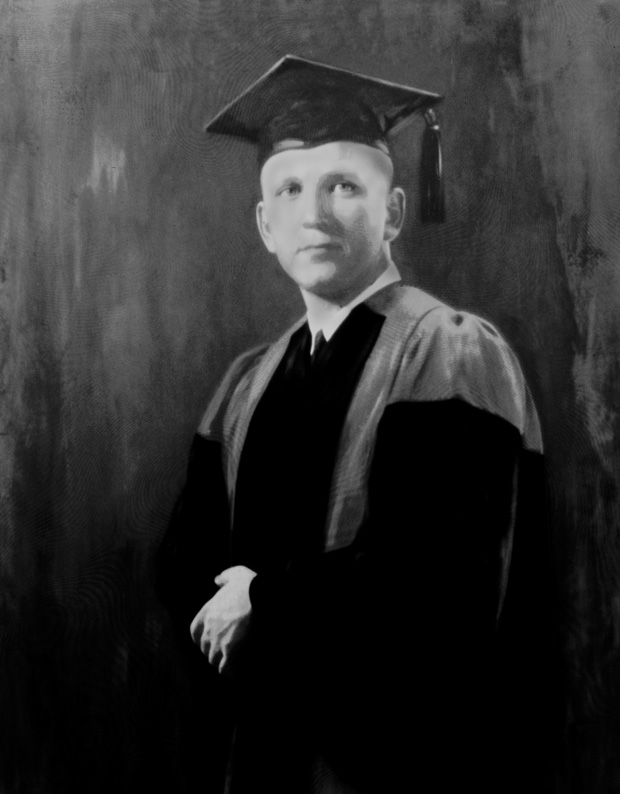

“I must have been about eight years old, standing on the front porch of my hometown of South Bend, Indiana,” he remembers of the moment he first heard the calling, as he conjures up visions of a sepia-toned America. “And I was waving at an open car bearing President Franklin Roosevelt to the University of Notre Dame to receive an honorary degree.”

His father Stephen had immigrated from Kalamata, Greece and ran a restaurant in Mishawaka, Indiana, his mother was named after Dante’s beloved, Beatrice Cenci, and she was a schoolteacher. “Her father was a history professor and taught classics,” says Brademas. “And as a schoolboy, my two brothers and my sister and I would spend the summers in a small central Indiana town of Chester Goble, had a library of about 7,000 books. And we lived in that library; we grew up in that library.” (The book he read on the Maya made him vow to “be a Mayan archaeologist. So I took Spanish classes in school and then as a high school senior I hitchhiked with a classmate to Mexico”).

Though Brademas was raised a Methodist, “My father inspired in us a great respect for our Hellenic origins,” he says. “When I would go to school and the other students would talk about their backgrounds, I could say, Well, my ancestors were Plato and Aristotle, what about yours?” In fact, his father had a motto that his son still quotes to this day in his speeches: “We Greeks invented democracy; some of us should practice it.”

Brademas was a natural politician and he practiced it from the start. “Even as a schoolboy I was active in the student council,” he says. “And in high school at South Bend Central High, I organized a mock national convention and brought together delegates from the other high schools for a mock national convention.” He went on to Harvard and then Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, “and at Oxford, I organized a mock Democratic national convention in 1952 and I wrote an essay for an Oxford undergrad paper, The Guardian, called “Why I’m Voting Democratic in November.”

It was a plea for the election of Adlai Stevenson as president, and the young politician sent copies to the candidate and to the office of Paul M. Butler, a South Bend lawyer who was the Democratic national committeeman for the state of Indiana. “And in 1953, when I was home in South Bend, I went to call on the most important Democratic in the district-and that was Paul Butler, and he remembered the article.”

He got more than 49% of the vote in that first campaign, but he lost by 2000 votes in a three-way race and he “knew coming so close that I would run again.” He bided his time by working for Stevenson in the summer of ’55 as his head of research on the issues (“And that was fascinating. I was the liaison to people like Paul Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith, Arthur Schlesinger–whose memorial I attended earlier this week”). And then he ran again in ’56—“and in ‘56 both Adlai Stevenson and John Brademas were a second time defeated. And I thought,” he says, “well here I am, I’m not yet thirty years old and I’ve twice been defeated for Congress–but I still thought I could win.”

Why politics, when as a Harvard graduate and Rhodes Scholar he could have written his own ticket? “I had strong convictions about the importance of politics,” he says. “Although my father was Greek Orthodox, I grew up in the Methodist church, which has a strong tradition of working for social justice. My late father told me when I was a child of how the Ku Klux Klan, which was important in Indiana at the time, had boycotted his restaurant in Mishawaka because he was not a WASP: a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant.”

After high school, Brademas joined the Navy because the war was still on, and he was stationed for training in Biloxi at the University of Mississippi, where he heard the notorious segregationist Senator Theodore Bilbo give a campaign speech. “Bilbo was the savage voice of segregation in this country and he made a speech in which he attacked Clare Boothe Luce and ‘those other Communists up north who would mongrelize the white race,” Brademas remembers. “That made a big impact on me and a few years later, now a member of Congress, I stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial behind Martin Luther King when he made his famous ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. And I worked hard in Congress for the Voting Rights Act and for civil rights and that was part of my motivation.”

On his third try in 1958 he was elected to the House of Representatives from Indiana’s Third District (which he served for 22 years) and from then on Washington, and John Brademas, would never the same.

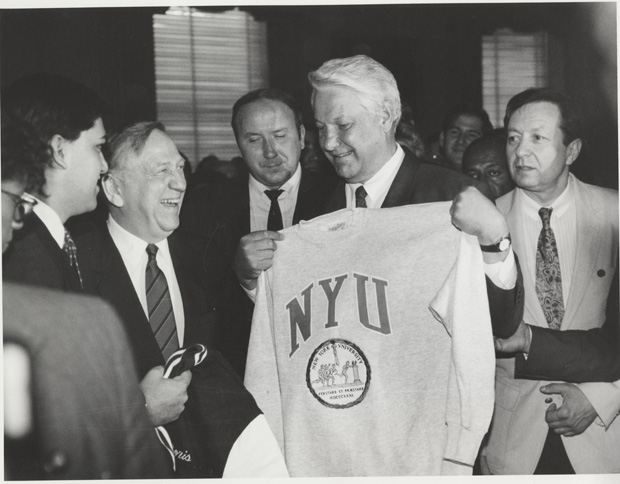

He served under six presidents, three Republicans and three Democrats, but he likes to quote legendary House Speaker Sam Rayburn on the role of Congress in the separation of powers. “Rayburn was once asked by a reporter, Mr. Speaker, under how many presidents did you serve? Rayburn: Under none. That’s a significant story about the American constitutional system and the separation of powers, because in our system, unlike a parliamentary system, Congress has power to make policy, national policy, independent of the Executive Branch. So if a Senator or Representative in Congress is knowledgeable and skillful, and if the configuration of political forces at that time makes action possible, that Senator or Congressman can, without picking up the telephone to call the White House, write the laws of the land, and I did, and others did. When you’re elected to the Congress of the United States that doesn’t mean you’re not supposed to talk to anybody else, any other public official, elsewhere in the world.” Brademas visited the Soviet Union as early as 1961 (and reminded Boris Yeltsin of that when the Russian leader visited NYU) and he led the first congressional delegation during the presidency of Jimmy Carter to visit the People’s Republic of China. “And I visited during my years in Congress, Poland, Hungary, Rumania, none of which was a democratic country during those times. I think it’s very important, given that we have a separation of powers, where Congress has the power to affect public policy, for members of the Senate and House to inform themselves by traveling to other parts of the world.”

And the young Congressman negotiated the halls of power with equal ease.

“Well, you must remember that when I came to Congress it was after my third campaign and that I had worked for a presidential nominee, my political godfather was the Democratic national chairman and I had previously worked on Capitol Hill. So although a freshman, I had somewhat more exposure to politics than other freshmen did. I felt a sense of confidence about what I was doing.”

Particularly important was getting a good committee assignment and he called up the Speaker himself to get the seat he wanted on Education and Labor: “I was in California on holiday after the election and I telephoned Speaker Rayburn, and I said, Mr. Speaker, this is one of your new students. I’m on my way back to Washington; can I come by and pay a call on you? Wonderful, when can you come? This was unheard of—there were over fifty new Congressmen elected that year.

So I went to Dallas, rented a car, drove up to Bonham, his hometown in Texas, and had lunch with the Speaker and he showed me his library there. And then he said, Well, I suppose you want to talk about your committee? He understood. I said, Yes, Mr. Speaker, I want Education and Labor. The Speaker: Hot potato committee, hot potato committee.”

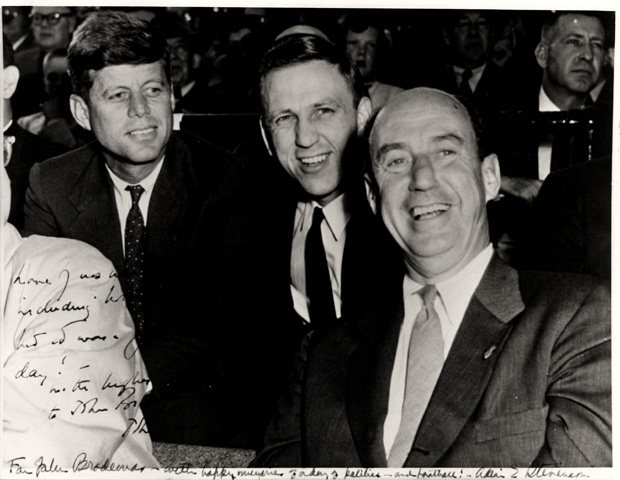

But with the support of Rayburn (and old mentors Paul Butler, since elevated to Democratic national chairman, and Adlai Stevenson) he got it. The hot issue then was labor reform (Brademas had the Studebaker and Bendix plants in his district) and a young senator named John Kennedy was riding the issue in the adjoining chamber. Brademas had worked summers in the Studebaker plant and knew the issues well and “there were those of us on the House education committee who were sympathetic to Kennedy, including me. In any event, I got my feet wet as a legislator, not in education but in labor reform.”

Brademas later occupied a subcommittee seat on an education subcommittee that Kennedy had occupied. “And I called on then-Senator Kennedy in 1960 and had a little chat. There was a kind of instant sympathy. We were both Harvard graduates, Bob Kennedy, whom I did not know at the time, actually attended Harvard with me. Senator John Kennedy came out to campaign for me in 1960. Then years later Ted Kennedy came and spoke at the airport for me. I’ve had these ongoing earlier this week at the memorial tribute to Arthur Schlesinger, who was on the faculty of Harvard when I was a student there.”

Brademas soon catapulted to the leadership after Hale Boggs appointed him a Deputy Whip and then Tip O’Neill made him Majority Whip in 1976. “I had a very good record with Speaker O’Neill. For one thing, he knew that I had studied at Harvard and Cambridge, a district he represented. In fact, years later, I was elected to the Harvard Board of Overseers and I said to Tip, Mr. Speaker, I’m spending more time in your district than you are. Harvard works her sons and daughters hard.”

Every Thursday morning at 9:30 the Majority Whip would chair a meeting of the Democratic leadership in the House and take a count. “And we would talk about the legislative schedule and the politics of it,” Brademas remembers. “Of course there you would have the Democratic Party represented from Mississippi to New York. And the Speaker would say, I would like to have a Whip check on HR 12345, whatever the bill was. What that meant was each zoned Whip, and one of them was Charlie Rangel, had a card and on the card would be listed all the Democratic representatives in that zone, and across the top it would read, yes, no, leaning yes, leaning no, undecided. The correct vote would be yes, meaning, yes, you are voting with the Speaker. And I would say, Let’s get a Whip check on this and get the information back by so and so.”

He thrived in the system and was slated in 1980 to become Speaker of the House after both O’Neill and Majority Leader Jim Wright had announced their resignation. But he had what he calls a “marginal” seat that he won every term against the odds (“I ran for Congress thirteen times, and only once did the people of my district give the majority to the Democratic nominee for President. That was Johnson in ‘64.”). Unfortunately, Reagan had his landslide in 1980 and John Brademas was out of a job.

“I enjoyed politics, obviously, and it would have been agreeable to be the Speaker,” he says philosophically. “But I was a grownup, I knew how these matters went and I spent every day in Indiana reading The New York Times. And in the Sunday New York Times News and Review section there’s the list of academic appointments, elections, health and medical school appointments and I noted one for NYU.”

So the day after the election, Wednesday morning, he remembers, “I telephoned the then-mayor of New York City, whose Whip I had been, one Edward I. Koch, and Ed said, John, I’m sorry, what are you going to do now? I said, I want to be president of NYU. And Koch said, alluding to our just defeated presidential nominee, If Mondale doesn’t want it, I’m for you. I was introduced to the chairman of the Board of Trustees, Laurence M. Tisch, and I took the job.”

He found NYU “a regional commuter institution—by regional I mean New York, New Jersey, Connecticut—and my objective was to transform it into a national and international residential research university. The year before my arrival we had raised, I believe, $23 million in private money. And I said for what was then already the largest private university in the country that was not acceptable, especially for one located in Manhattan. So I announced a goal of $1 million a week in private contributions for 100 weeks and we did that. And then I set in 1984 a new target of $1 billion in private contributions by the year 2000—and we did that in ten years. With those funds we were able to carry out that transformation. I’m pleased that according to the Princeton Review, I believe, for the last four years or so, measured by the number of students who apply for admission, NYU has become the most popular u in the U.S.”

He smiles, “And I know at least once a week I get a letter from some Greek American family wanting me to help get their sons and daughters into NYU. And I just say, Well, just make sure they’re very good students.”

Now president emeritus of the university (he retired in 1992), he’s still very active at the school and his “major project” now is the John Brademas Center for the Study of Congress.

“With 100 Senators and 435 Representatives and without the strict party discipline characteristic of European parliamentary systems, it is difficult even for informed Americans to understand the U.S. Congress,” he says. “So what we are doing at the Center is organizing symposia and lectures on the processes by which Congress makes policy and important issues of policy.”

There was a lecture at the Library of Congress introduced by James H. Billington, the Librarian of Congress, and Senator Richard Lugar, former chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, who spoke on the role of Congress on foreign policy, and Senator Paul Sarbanes, who spoke on Congress and domestic policy. There was a subsequent lecture by Professor Robert V. Remini, author of a history of the House of Representatives; and a recent conference which included former Senator Bob Kerrey and former Nixon White House counsel John Dean. And Brademas now hopes to organize a symposium on the Speakership of the House of Representatives, “to which I would invite Nancy Pelosi, Dennis Hastert, Newt Gingrich, Tom Foley and Jim Wright, all Speakers, to discuss this institution in the American constitution because it’s not really well understood.”

The center is housed in the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and “is wholly bipartisan,” he says. “I have an advisory council on which there sit senators and congressmen, sitting and former, Democrats and Republicans.”

Brademas himself, of course, never sits for long. (His wife Mary Ellen is a dermatologist and he has no children of his own. They live in the residence across from Washington Square Park.) Near the end of the interview he’s already checking over his pocket to-do list and flipping through his master list in the folder he’s always carrying.

“I have plenty to do,” he says, “and I have more opportunities to make speeches and write articles than I need. I think I have been blessed by the opportunity to have several careers. And now in effect I have a third life in a bouquet of various activities.”

He consults his pocket to-do list, and we’re off.

0 comments