- Leading HANAC: Stacy Bliagos on Community Service in New York

- The Hellenic Initiative Celebrates Record-Breaking Weekend in New York

- Building the Future: HANAC’s 53rd Anniversary Gala Honors Advocates for Affordable Housing and Community Care

- Leona Lewis: Las Vegas residency ‘A Starry Night’

- Emmanuel Velivasakis, Distinguished Engineer and Author, Presents His Book at the Hellenic Cultural Center

Greeks and The Anti-Semitic Pogroms of Odessa

by Dean Kalimniou*

Odessa entered the nineteenth century as an imperial experiment. Founded in 1794, on the site of an ancient Greek colony, it developed rapidly into a major Black Sea port whose population was shaped by trade, mobility and imperial privilege. Greeks and Jews, fleeing persecution and seeking opportunity, arrived early and settled in large numbers. By the 1820s, both communities occupied prominent positions in the city’s commercial and social life. Greek merchants dominated shipping, brokerage and international trade networks while Jewish traders, artisans and middlemen expanded steadily within retail, finance and grain export. Proximity and competition were unavoidable.

The first major rupture between the two groups occurred in 1821. Its timing concerned itself with events taking place far beyond Odessa. The outbreak of the Greek War of Independence and the execution of Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory V in Constantinople reverberated across the Orthodox world. Odessa, home to a politically active Greek diaspora and to members of the Filiki Eteria, became a centre of intense agitation. Greek refugees arrived from Ottoman territories bringing accounts of violence, executions and reprisals. Within this charged atmosphere, allegations circulated that Jews in Constantinople had assisted Ottoman authorities during the patriarch’s execution and indeed, had agitated in favour of it. These claims were repeated in the Greek coffee shops and clubs of Odessa with increasing insistence.

The burial of Gregory V in Odessa, after his body was fished from the sea in June 1821 provided the immediate setting for violence. Contemporary observers describe unrest breaking out during the funeral procession itself. The German writer Heinrich Zschokke, who was present in the city shortly after the events, recorded that Greek attacks on Jewish homes and shops occurred simultaneously in several districts. Windows were smashed, shops looted and individuals assaulted. The main synagogue was damaged. According to later reconstructions based on municipal records, seventeen Jews were killed and more than sixty were injured.

Imperial forces were deployed, though their role proved ambiguous. Zschokke reported that soldiers and Cossacks intervened unevenly and that looting continued in their presence. He further noted that advance warnings had circulated among Jews advising them to remain indoors, suggesting foreknowledge on the part of local officials.

The 1821 pogrom was treated by the authorities as a disturbance linked to extraordinary circumstances. No structural measures were put in its place to prevent later re-occurrences and the event was soon forgotten, its memory remaining largely confined to the Jewish community. Within Odessa’s Greek milieu, the episode was subsumed by narratives of martyrdom and national awakening.

Over the following decades, economic relations in the city changed significantly. The abolition of Odessa’s free port status in 1859, combined with the aftermath of the disastrous Crimean War, weakened Greek mercantile dominance. Jewish firms expanded into areas vacated by Greek trading houses. By the middle of the century, Jewish traders were prominent in grain export, retail and finance. Statistical surveys from the 1860s show Jewish ownership increasing steadily across commercial sectors. Greek commentators and merchants registered this shift with ever growing resentment.

A second pogrom targeting Odessa’s Jewish population occurred in 1859, during the Orthodox Easter period. Its immediate catalysts lay in the circulation of rumours rather than in any identifiable political event. Jews were accused of ritual murder and of the desecration of a Greek Orthodox church and cemetery, allegations that drew upon long-established European antisemitic tropes.

In subsequent correspondence, Governor Alexander Stroganov attributed the outbreak of violence to religious fanaticism amplified by the spread of false reports.

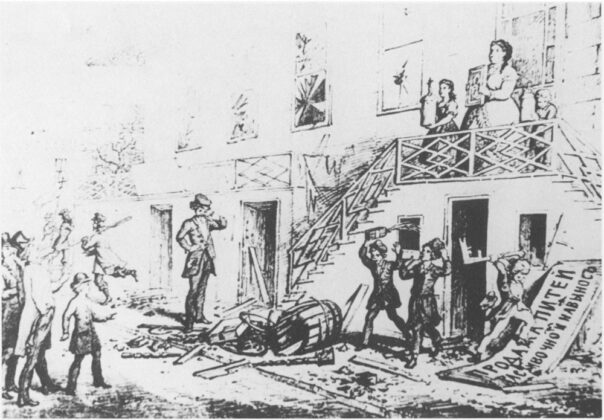

Violence broke out among groups of Greek sailors and dockworkers, joined by local residents. Jewish homes and shops were systematically attacked. Contemporary accounts differ as to the number of fatalities. Some sources report one Jewish death, while others record two. Several individuals were seriously injured. Property damage was limited compared to later events, though the symbolic significance was considerable. Local newspapers described the episode as a street fight, avoiding the language of communal violence. Once the tumult had abated, the administration treated the matter as resolved.

By the late 1860s, Odessa had emerged as one of the Russian Empire’s largest Jewish urban centres, a transformation accompanied by the growing prominence of Jewish entrepreneurs within the city’s commercial life and the corresponding decline of Greek firms. Within the Greek community, these shifts were increasingly experienced as displacement and loss, and responsibility for economic decline was frequently attributed to Jewish competitors. As a result, tensions hardened, and economic resentment found expression in religious language. Pamphlets circulated accusing Jews of exploiting Christian labour and mocking Orthodoxy, while the memory of Patriarch Gregory V was revived, often detached from its historical context and redeployed as a symbolic instrument of grievance.

Against this background, the pogrom of 1871 unfolded over several days and marked a qualitative escalation in the pattern of violence. It erupted again during Orthodox Holy Week, apparently triggered by a minor altercation whose precise circumstances remain unclear in the surviving sources. What can be established with greater certainty is that organized groups quickly coalesced and directed their actions toward Jewish districts of the city. Contemporary reports and subsequent investigations identified Greek merchants and agitators as the principal organizers, and the violence spread in a methodical manner, with Jewish taverns, shops and homes subjected to widespread destruction.

Municipal records and eyewitness accounts indicate that more than eight hundred homes and five hundred businesses were damaged or looted, leaving thousands of Jewish residents displaced. Official casualty figures recorded six Jewish deaths and twenty one injuries, although some contemporary Russian reports sought to minimize the number of fatalities. The scale and pattern of destruction suggest a degree of restraint in the use of lethal force, possibly shaped by a prevailing assumption that the authorities would tolerate extensive property damage while intervening decisively only in cases of murder.

The response of the imperial administration was marked by hesitation and delay. Governor General Pavel Kotzebue refrained from ordering decisive military intervention during the initial stages of the violence, while Jewish self defense groups were dispersed by police and Cossack units rather than permitted to protect their neighbourhoods. In this atmosphere of uncertainty, a rumour circulated among the rioters that imperial permission had been granted to destroy Jewish property. One Russian eyewitness later recalled a remark attributed to a Greek participant in the violence: “Do you think we could destroy and beat Jews for three whole days if that had not been the will of the authorities?” Order was restored only once the unrest began to extend beyond Jewish districts and to threaten the stability of the city as a whole.

Arrests followed in the aftermath, with approximately six hundred individuals detained, largely drawn from the urban poor. No prominent organizers were subjected to serious punishment. Official reports attributed the pogrom to intoxication, religious passion and class resentment, and an internal memorandum explained the hostility as arising from perceptions of Jewish economic dominance combined with religious difference. The language employed in these assessments avoided any sustained consideration of structural or systemic factors.

Jewish intellectual responses were swift and documented. Writing in Odessa in 1871, the jurist Ilya Orshansky framed the events in legal and structural terms: “Until such time as the divergence between the Jews’ actual and juridical position in Russia is permanently removed by eliminating all existing limitations on their rights, hostility to the Jews will not only persist, but in all likelihood will increase.” His assessment circulated widely within Jewish legal and journalistic circles.

The journalist Mikhail Kulisher approached the pogrom from a psychological and historical angle. Reflecting on the events, he observed that “beneath the apparently accidental and singular Odessa pogrom we discovered something of enduring importance, namely, that Judeophobia was not a theoretical error of some kind, but a psychic attitude in which centuries upon centuries of hatred was reflected.”

Taken together, the three Odessa pogroms form a discernible pattern rather than a series of isolated disturbances. Across all three outbreaks, rumours framed in religious language circulated amid periods of economic transition, frequently coinciding with moments of heightened liturgical intensity, while administrative hesitation operated as a permissive condition. During this specific phase of Odessa’s history, the Greek community emerged as the principal initiator of anti-Jewish violence, a role that diminished after 1871 as leadership of pogrom activity passed increasingly to Slavic populations and organized far-right movements. In this respect, Odessa bears comparison with earlier imperial cities such as Roman Alexandria, where Greek and Jewish communities similarly competed for proximity to power, civic privilege and economic advantage, and where violence repeatedly erupted at moments when imperial authority proved ambivalent or strategically disengaged.

In Odessa, as in Alexandria, communal conflict unfolded within an imperial framework that rewarded intermediaries. Greeks in southern Russia had long functioned as favoured Orthodox agents of empire, occupying a position shaped by commercial utility, religious affinity and political expediency. This alignment afforded privilege, yet it also rendered the Greek community vulnerable to instrumentalisation. While direct state orchestration of the pogroms cannot be demonstrated, the pattern of official hesitation, selective enforcement and subsequent narrative minimisation suggests that Greek hostility toward Jews operated within tolerable bounds of imperial policy, serving at times to deflect social tension and to regulate competition without destabilising the broader order.

The consequences of this history extended beyond its immediate Jewish victims and profoundly shaped the Greek community itself. As Greek mercantile dominance declined and imperial favour became less secure, Greeks in Odessa came to occupy an increasingly ambiguous position within the Russian state. Following the Russian Revolution and civil war, the Greek population of southern Russia would abandon the region in large numbers, dispersing to Greece, the Balkans and the wider diaspora. In exile, memories of Odessa were selectively reordered. Narratives of prosperity, philanthropy and national awakening were preserved, while episodes of communal violence were marginalized or omitted, failing to enter the usable past through which displaced Greek communities articulated their twentieth-century identity.

Greek-language sources from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries reflect this process of selective remembrance. Memoirs, communal histories and publications produced by Greek Odessans tend to emphasize educational institutions, churches, benefactions and revolutionary activity, frequently portraying the city as a site of harmonious coexistence later disrupted by Russian or Bolshevik violence. Where conflict is acknowledged, responsibility is diffused or reframed through the language of disorder and popular excess. The Greek role in earlier pogroms against Jews is rarely examined directly and, when mentioned, appears obliquely, stripped of agency and historical specificity. Silence thus functioned as a mechanism of communal self-preservation.

Within Odessa’s historical archive, these events occupy an unsettled position. The city’s reputation for cosmopolitanism endured, though fractured by episodes of collective violence that resisted incorporation into celebratory narratives. Greek and Jewish histories remained intertwined through commerce, language and shared urban space, even as trust was eroded and reconfigured. The pogroms did not extinguish Jewish life in Odessa, yet they altered its orientation, accelerating migration and sharpening political consciousness. At the same time, they contributed to a Greek diasporic memory shaped by loss and displacement, one that increasingly preferred to recall itself as victim rather than as an earlier participant in the exercise of communal power.

The Odessa pogroms therefore illuminate more than a sequence of anti-Jewish attacks. They reveal how imperial structures fostered competition among minority intermediaries, how privilege could be extended without protection, and how violence could be absorbed into administrative routine and later effaced from communal memory. As in Alexandria under Rome, coexistence rested on contingent favour rather than secure equality. The archival record that survives remains incomplete, reminding us that the histories communities carry forward are determined as decisively by what is set aside as by what is remembered.

*) Dean Kalimniou (Kostas Kalymnios) is an attorney, poet, author and journalist based in Melbourne Australia. He has published 7 poetry collections in Greek and has recently released his bi-lingual children’s book: “Soumela and the Magic Kemenche.” He is also the Secretary of the Panepirotic Federation of Australia.

0 comments