- Leading HANAC: Stacy Bliagos on Community Service in New York

- The Hellenic Initiative Celebrates Record-Breaking Weekend in New York

- Building the Future: HANAC’s 53rd Anniversary Gala Honors Advocates for Affordable Housing and Community Care

- Leona Lewis: Las Vegas residency ‘A Starry Night’

- Emmanuel Velivasakis, Distinguished Engineer and Author, Presents His Book at the Hellenic Cultural Center

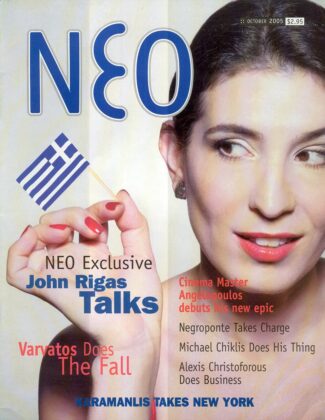

THE NEO STORY

How a grassroots effort twenty years ago became a lasting part of the Greek-American community and worldwide Greek identity

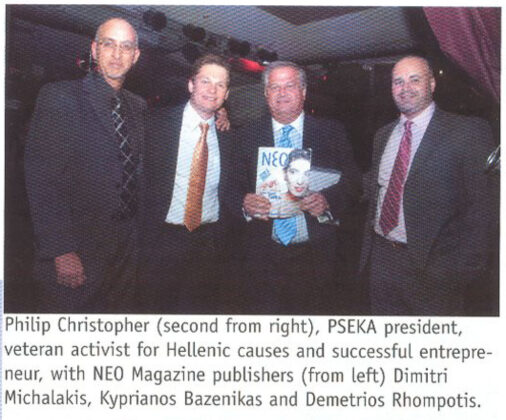

At the outset, we were lucky to find the right people to bring NEO Magazine to life. Kyprianos Bazenikas, now a successful businessman, was the third of our founders. Thanasis Harmantzis, known as Tommy, a retired businessman, became the magazine’s driving force, seeking ads and new people and managing to be everywhere, sometimes at two different places at the same time—a pillar of this effort.

And Adrian Salescu, our designer, who’s been with us almost from the beginning and has shaped the visual identity of this magazine. Kelly Fanarioti and Athena Efter, chief among our always-dogged and enterprising writers and contributors. Our photographer in residence, the legendary and beloved-to-all, Fotis Papagermanos. Not to forget our printing brother-in-arms, Ed Scheibel, who has kept us in print all these years.

Before these wonderful people joined our crusade, I happened to know Dimitri Rhompotis, because we both worked in the Greek press in New York for many years. And you couldn’t miss Dimitri, because he usually wore a Panama hat like a Colombian coffee plantation owner, and no cigarette would do for him: he smoked a cigar like he just came from his coffee plantation in Lefkada.

When we both worked at one of our Greek papers together, he would show up after lunch with one of the fat bagels he picked up at the local bagel store and offer me some, because we called them “truck tires.”

I heard rumors that he was a poet, besides being a journalist, a man who knew about most things, and just about everybody. You asked him about anybody and he would thunder forth in what Kyprianos once teased was his “radio announcer voice.”

He would use his radio announcer voice to have monologues about most things, at most of the cafes in Astoria, but particularly at his throno at the Lefkos Pyrgos Café on Ditmas Boulevard, where conversations were never private, and Dimitri would have conversations with several people across the room all at the same time.

It was politics, it was personal, and it was anything that Dimitri would think to declaim in his radio announcer voice, which sounded very much like a Greek radio that was perpetually on.

And then one day, when both he and I were covering a politician making a campaign stop at one of the Astoria parks, we stood next to each other waiting for the politician, and I looked at him, and he looked at me (probably under his Panama hat).

“What are we doing here?” I told him. “Why don’t we start our own newspaper?”

“Yes,” he told me in his stentorian tones, “the question is how?”

And then we forgot about the newspaper, and decided we wanted to start a magazine, which was even more ambitious. And it remained only an ambition, but Dimitri, who knew everybody and the praktika of the business, was the one who actually made it happen with Kyprianos, who knew how to get ads and the people who placed them to pay for them.

And what to call it? I remember the debate with Dimitri and Kyprianos until we broke down what we wanted the magazine to be: a place where the young and old of our community could come together and find out about each other. A new beginning in communication—and so we called our magazine—NEO.

Soon we were visiting a printer in Greenpoint, a Greek, who might become a partner, in return for his services, only the discussions soon escalated into a Greek discussion—where you couldn’t tell the difference between talking and yelling.

Dimitri was in the trenches for that, but the partnership didn’t last long with that Greek printer, although the printer’s mother was there at the office to offer us coffee, and she was very nice.

The magazine got off the ground nonetheless, and there was the friend I had in Long Island who would do our layout and had a staff of professionals. I remember making trips to visit him and being impressed with his office, even if his mother wasn’t there serving coffee. Unfortunately, that partnership didn’t work, either (not my friend’s fault), but still we soldiered on.

There were meetings in Astoria, at various coffee shops, Dimitri presiding and declaiming as each issue took shape, or at Kyprianos’ backyard, and the both of them performing miracles of revenue and footwork to get each issue printed and distributed.

Meanwhile, with Dimitri scanning the landscape for stories and giving his input at out coffee shop conferences, I would in the early days try to put the issue together, and give it a tone and a voice. And I would trek up the stairs every week to the Manhattan apartment of our first layout man and huddle over his computer to put it together. He was very patient with me, and we kept experimenting, while I asked him to do the impossible and make the magazine look like it had a million-dollar budget when we had only the latest revenue that Dimitri and Kyprianos could manage to flog from our latest advertisers.

But somehow those first issues came out, and Dimitri and Kyprianos hustled to distribute them to newsstands everywhere (in those days when print still mattered) and suddenly our new magazine—NEO—was on the stands most everywhere in New York City.

And the subscriptions kept adding up: I remember going to our mailbox and seeing the new subscriptions and checks and coming out with a smile of triumph on my face. Because how many times has a Greek magazine been tried in America and how long has it lasted? The graveyard of such publications is acres wide and their yellowing pages can be found on many a cigarette machine (remember them?) in every Greek restaurant.

I remember working at one Greek national newspaper with ambitions to rival the other Greek national newspaper, which actually had nice offices, and actually had a good staff, and looked like money was being invested in it—and it lasted a few years—until it slowly began to wither. I wrote a letter to the publisher, a wealthy man doing this as a duty to the community, suggesting how the effort was worthy, don’t lose steam, this is how it could keep going and do even better. I was in the business for years, I had worked for Greek publications for decades, a whole string of them, and yet there was still a vacuum, and our community deserved better.

No reply, the newspaper predictably died the slow death of the many before.

So how was our magazine going to survive—against all the odds?

But we fought the odds.

There were countless times in those early days when we would visit people and make our pitch. We could even fly to San Franscisco or Denver and back the same day, taking advantage of the time difference.

I remember us driving at night to huddle with a very nice man under a bridge in his work trailer as his company refurbished the bridge. We told him how he could help the magazine and how the magazine could help him. He was a proud Cretan and we appealed to his native pride and told him how it could highlight the many wonderful Cretan products and Cretan culture for our new generation—the very purpose of the magazine.

He listened politely, he smiled kindly, we left the trailer, we heard nothing from him.

I remember my cousin in Baltimore suggesting I visit Baltimore and talk to a friend of a friend who had been a publisher for years (had even run for governor and later tried to buy The Baltimore Sun). The friend of the friend would arrange for me to have breakfast with the publisher and see if an alliance could be made.

So I left at the crack of dawn for Baltimore, got there in time for breakfast, met my cousin, and then over the clatter of breakfast dishes, and the appeals of the friend of the friend, the publisher listened to me patiently, hands stacked, his toast and eggs and bacon waiting, and then told me, from his experience, that a Greek magazine like ours would cost over a million dollars to get off the ground.

I told him it was off the ground already and was fueled by sheer enthusiasm and hard work.

He heard me, he kept his hands stacked, his eggs and bacon getting cold, but repeated what he told me, and then started talking shop talk and local gossip with the friend.

I thanked my cousin and couldn’t back to New York fast enough.

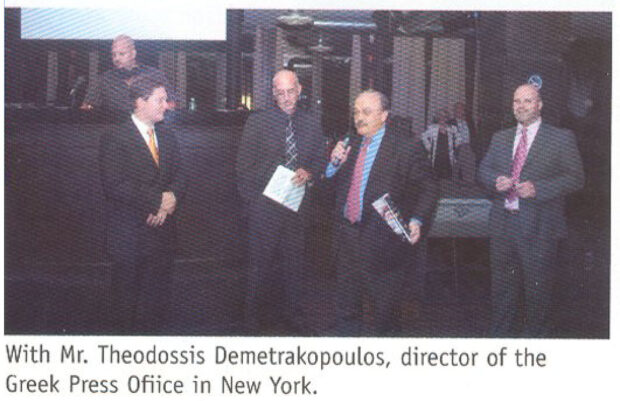

2005, at NEO’s inaugural event.

The friend of the friend did try again another time, he was a good friend and a mover and shaker in Baltimore (he also ran for governor). And this time he told my cousin to invite me to Baltimore for a beauty pageant where I would be a judge, and, at the same time set up some meetings for me with Baltimore movers and shakers. I went, I judged the beauty contest with others, and then got down to business at the dinner afterwards by the lights and sparkling windows of the beautiful Baltimore waterfront.

Where I huddled with the movers and shakers, and one of them, with lively eyes and a mustache like Karaiskakis asked me what made our magazine different.

“Because it’s American,” I told him, “and published in America, with our ears to the ground, and in direct touch with our community. It’s not put together in Greece and given an American title. It’s put together here, and not distributed only to the members of one community or one organization. It’s for every community in America. And for the young and old, and written in English, so the younger generations can access it easily.”

I talked and talked, while the man with the lively eyes and the Karaiskakis mustache popped his eyes and looked amused by my passion, only the friend of the friend’s smile looked pleased.

So I went on.

“Where are the magazines that bring the generations together?” I told them, shoving aside the bread basket and relish tray. “How do the young people find out about the papoudes and yayades and what their parents went through when they came to America, and how do the papoudes and yayades find out about what their children and grandchildren are doing? We want to bring the generations together so we have a common Greek forum!”

The man with the Karaiskakis mustache twitched it a little, the friend’s eyes roamed: either I had them or I didn’t.

I drove back to New York.

I didn’t have them. A few subscriptions dribbled in, mostly through the efforts of my cousin, and we did a special issue on Baltimore and everybody was nice.

But the movers and shakers were not moved.

But somehow our magazine was taking hold and soon we had notable events. Like our coming-out party in Astoria with family and friends, a whole banquet hall of them.

And our Person of the Year celebration with soon-to-be Congressman John Sarbanes of Maryland, and Senator Paul Sarbanes attending, at one of Manhattan’s fabulous new restaurants. John Sarbanes spoke, Senator Sarbanes spoke (the nicest man in the world, and his wife equally nice), and former House Minority Whip John Brademas, who we profiled in a later issue.

We were even featured in the Greek press and interviewed by Greek TV, where I repeated my mantra.

“We are doing this to bring the generations together, the young and the old,” I said. “Isn’t it about time?”

And we kept on, with our café conferences in Astoria, after work or the weekends, where Dimitri used his radio announcer voice to inspire us and keep us on track, and I had a conference of my own with a mover and shaker I had met in Baltimore and was based in DC and gave me hope we were getting the attention of the people who considered us important enough to have lunch with.

I asked the mover and shaker to be our DC correspondent, he agreed, and I thought we had arrived.

He did a few columns, he was a busy man, he moved on.

I talked to a man in Manhattan, a refrigeration tycoon, at a restaurant he had invested in, and I told him about the magazine, and then told the young owner of the restaurant about the possibilities of a magazine like this that would serve the new generation like him.

The young restaurateur was very nice and polite, we even featured his wife on one of our first covers.

Only the refrigeration tycoon went on to dream about building golf courses in Greece and the young restaurateur was more concerned about his restaurant.

Still we soldiered on.

Dimitri drove everywhere, Kyprianos drove everywhere, to talk up the magazine, I drove to places to give talks and get people to subscribe, a big thing in those days.

2005, at NEO’s inaugural event.

I remember going to Manhasset one night for a meeting of the Manhasset Greeks, who were very nice, and they heard me out between their coffee and cake, in the hall of church, and I gave them my spiel.

“Don’t you want to find out more about your kids and grandkids? Shouldn’t your kids and grandkid find out more about you?”

They listened, I got to talk to many of them, one doctor was very thoughtful about our effort, and they inspired me with the wealth of good and accomplished people we had in our community.

Maybe a few subscriptions there.

Another time I drove with my wife to a meeting of a Greek civic group in New Jersey, which turned out to be in a trailer, Dimitri had joined us, and we talked a good talk to the group: Dimitri kept them awake with his stentorian voice. But after the coffee and cake, the man in the front row began to doze off when I began to speak.

No subscriptions, that I know of.

Those were our early efforts, where getting these subscriptions was so critical. Those efforts seem a relic of the past now: we have a website and now everybody can see us worldwide

And see that with the redoubtable efforts of Dimitri Rhompotis and the key people I mentioned that have kept us publishing, and still here after twenty years, profiling the most interesting people in our communities not just in America, but abroad. Kelly Fanarioti most recently interviewed a young woman from New York City who went to Greece, fell in love and stayed, and revived an entire village and made it thrive with her native Greek husband.

There are Greeks doing wonderful things everywhere all over our Greek world, just as we found so many over our twenty years of publication right here in America.

There was the candle maker in Astoria who, as a matter of conscience, would visit the trouble spots of the world to bear witness: an ordinary man risking his life to advocate for justice.

There was the poet, who made donuts by day, and wrote poetry of the most soaring lyricism and deepest passion by night: a Cavafy of the heartland.

There were the loving couple who had worked together all their lives and were a mainstay of their community, and when one of them died, the other one was left heartbroken, but soldiered on with the help of the community he and his wife had fought so long and hard to support.

There was the mixed marriage couple who were an industry in themselves: she wrote mystery novels, and he was a restaurateur/dancer.

There were the folks in Arizona who set up their own ancient Greek theater on the grounds of an American university, and at their expense, presented the ancient tragedies with trained actors, under the stars.

There was the Greek comic who gave up a prosperous career to go on the road and do standup throughout North America talking about our Greek American life: like his mother stopping the car on the side of the highway to get out and pick horta.

There was the sister of Pete Sampras, who was a noted tennis player in her own right, and who talked about their rivalry when they were growing up, turned into newfound respect and support when she became the tennis coach of her university.

And there was the story of my father, which I wrote shortly after his death, as a tribute both to him and the epic generation he represented: our greatest generation that had survived war and immigration and had come to America to flourish on its own, but also to give the future generations a better life.

These are stories that we told in NEO over our twenty years, and there are so many more to be told over the next twenty years and beyond, when hopefully a new generation will take up our effort and continue this journey more successfully along with our community.

We want to thank everybody who has contributed with their support, personal effort, and ads to this project. Thanks to you we made it to twenty years and you have every right to share this accomplishment! This is not a business like any other: it’s a collective effort that works for the common good. We were in this together for twenty years, through all our efforts, and together let’s make it another twenty years and more.

0 comments