- Leading HANAC: Stacy Bliagos on Community Service in New York

- The Hellenic Initiative Celebrates Record-Breaking Weekend in New York

- Building the Future: HANAC’s 53rd Anniversary Gala Honors Advocates for Affordable Housing and Community Care

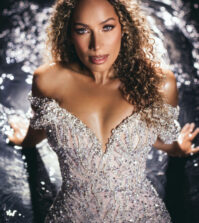

- Leona Lewis: Las Vegas residency ‘A Starry Night’

- Emmanuel Velivasakis, Distinguished Engineer and Author, Presents His Book at the Hellenic Cultural Center

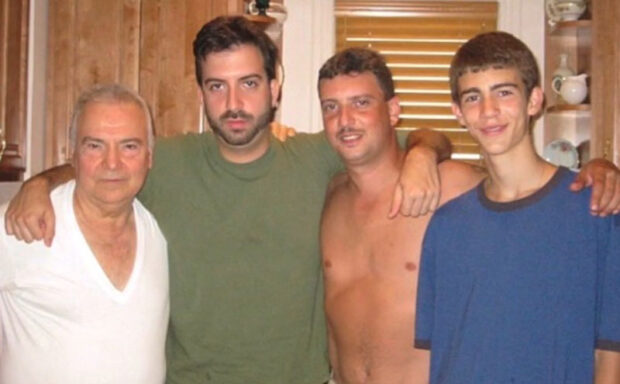

Mario Michalakis: An Immigrant Success Story

(My brother-in-law passed away a few years ago. He came to America, worked hard and became a success, raised a family, and was both a friend and big brother to me)

I first met my future brother-in-law Mario at the Bay Crest Restaurant in Brooklyn, where he would come in for lunch between his work as a landlord of several buildings in the area, and with his customary work clothes on, but spotlessly neat.

You couldn’t miss Mario (last name also Michalakis), with his hawk eyes and hair cropped short (he later told me he made a fetish of brushing his hair a hundred strokes every day and showed me the brushes to prove it), and a voice that could be soft and attentive, but get loud as a buzzsaw when he got excited or laughed.

In those early days in the ’60s, when I was around twelve, I was the summer dishwasher at the restaurant, which my family co-owned with our cousin Mike Mallas. And Mario would show up and perch on a stool and we would get into conversations, on my way to get a squirt of seltzer from the soda fountain or a soda, before I plunged back into the kitchen. Or during a longer break, we would sit at one of the booths and he would listen to my kid tales, and I would listen to his story.

His father Nicholas had been a merchant seaman from Kardamyla in Chios (and he worshipped him), but when he died from a heart condition after the war, the family was shuttled to a series of refugee camps run by the British in Egypt and Ethiopia, where they survived for years through the toughness of his mother, Evdokia. Until he was old enough to work on the ships like his father, reach America, and jump ship in Virginia, before he met up with relatives in Ohio, worked in a factory, and then joined other relatives in Brooklyn and worked in restaurants.

Only he was caught and deported, but then he came back legally, married and had a child, but that marriage dissolved, and for a stint he worked as a tool-and-die maker both in Brooklyn and Long Island.

But Mario was smart and ambitious, and soon he was buying property in Brooklyn, first a house on Third Avenue, then another on Senator Street, where the tiny Danish lady on the first floor, Marie Overgaard, became both his friend and adopted aunt of the family, and the matron of the building (forever chasing the cats out of the garbage).

Buying one building led to buying another, and I remember he was forever juggling houses and mortgages, and talking to “Mr. Minor” for credit on his next oil delivery, and “Sigountos” for his real estate transactions, and “Manolis” for his legal work, double-parking everywhere and making himself one of the business landlords in Brooklyn, while he built up a life that was all his own.

Because Mario was nothing if not independent.

He was the only Greek I knew, and one of the few people in Brooklyn, who actually drove a Rambler in his early days as a bachelor, with custom slipcovers, immaculate floor mats, and the first sugarless gum I ever tasted that he kept in packets in the glove compartment.

So the car in those days always had the distinctive smell of sugarless gum.

And then one day, after our talks by the counter of the Bay Crest Restaurant, my sister Helen, who worked as a waitress and hostess, asked me my opinion of this guy, Mario.

We were at our house, on Parrot Place, in the kitchen, I think she was getting our dinner ready, and the question was casual.

Yeah, he’s a nice guy, I think I told her casually.

Only then my sister brought my dinner and asked me more about this guy Mario.

So he’s a nice guy, right? she said.

I said he was, and got down to dinner.

And suddenly Mario became a part of our life, always crisp in his workmen’s khakis, unless he got dressed up in his innumerable coordinated outfits with Hush Puppies as he took us for evening drives to Kennedy Airport, down the Belt Parkway, to the blizzard of lights at the airport, like a perpetual Christmas, and to the garden by the parking lots that had benches. And there we would sit and ogle the people that would get out of cabs and hustle into the terminals to fly to the romantic parts of the world, and share the romance with them, even though we weren’t going anywhere.

I remember Mario picking us up in the Rambler on this and many other outings, scrambling around to open the door for my sister, like an old-world gentleman, while she stood there like a lady and waited, and I sat in the back seat with my mother and waited impatiently for the whole ceremony to finish. (My father worked in Chicago at the time).

And in the Rambler we would cruise through the streets of Brooklyn to the airport, or some nights, on a whim, he would pack us up and drive us out to Long Island to have some “parea” with our Thio Stelio, which I remember was a feast of fruit and nuts and coffee and “astia” and “yelia” around the table, before the drive back on the expressway, with the radio playing soft music, the dashboard glowing, and me drifting in and out of sleep.

One summer when my dad was here for the summer, I remember we drove to Jamesport, Long Island for a getaway, where we strolled to the beach every day lugging our blankets and cooler, and Mario wore his summer coordinated outfits with the Hush Puppies, and one time he made plans to go fishing with Mike Mallas in a rowboat and remember his old seafaring days.

Back in Brooklyn, he would take me every Wednesday to Carvel to get the two-for-one sundae special, and then the two of us sit in the Rambler and lap it up. In return, I would be his designated live body when he double parked to visit the bank, or “Sigountos,” or the plumbing supply store to get “vides” and “peepes.”

Or I would be his kid helper holding the wrench and flashlight as he fixed the leaky pipe in somebody’s bathroom (with the flowery shower curtains, and the clothes hanging from them), or some grim basement like a coal mine, where some asthmatic furnace was breathing its last.

Only then when he got through with his work day, Mario would often help me with my math homework–I hated math–but Mario loved it, and suddenly my math homework would become immaculate, until the teacher got so impressed that she started asking me questions in class, while I sat there frozen like a popsicle.

I remember the science project she asked us to do, only I was hopeless in practical things, too, a family trait: my grandfather in Greece once built a ladder too heavy for him to carry. Only for this science project, Mario decided to help me and he created a masterpiece: this elegant and simple display of magnetism on a wooden board, with a spool of orange wire, that would attract a metal piece when you tapped a button, and it was beautiful.

I put my name on it, brought it proudly to class, and my teacher got so impressed again (she didn’t learn her lesson from my pretending to know math) that she entered it in the Science Fair, where I won a prize (actually Mario), and then the teacher kept it in the classroom for weeks afterwards to show that even a science dunce like me could turn my life around.

And it remained in our basement for years afterwards and never stopped working: it was immortal.

He also used to drive me to church in the morning, Kimisis Theotokou in Sunset Park, where I was an altar boy, and he would scoot off again (he was not a big churchgoer). And I remember one night he and my sister picked me up from an Easter service, and as I sat in the back seat I told them all about the visit of the Bishop for the service and how his sermon addressed the story of Christ’s agony on the cross, complete with vocals.

“Me tin foni tou pano—” the Bishop thundered at us theatrically “—aaf, oof, eef!”

And as I thundered it from the back seat of the Rambler, Mario started laughing and couldn’t stop and I was proud I could make him laugh so much.

Another time, I told him confidentially (cause now we were buddies) about the night I was supposed to go to sleep when my mother had gone out with them, but I got up instead and watched The Rat Patrol and Dean Martin, until I heard them coming back, so then I made everything “cold” again and tumbled into bed.

And Mario started laughing and couldn’t stop about how I made everything “cold” again.

Eventually, Mario and my dad got into the restaurant business together, which Mario didn’t want, but he did it for the family, and I remember the countless nights all of us spent at The Colony House on Fourth Avenue, where Mario made himself go back into the kitchen and give up his independent life for us.

It was hard for him, but we were at The Colony House when he married my sister and we had the reception in the big room with the mirrors and fancy chandeliers, and the place became my second home. I worked there as a dishwasher (of course) and bus boy after school, and the staff there became my second family: Mike, the bartender, with wavy hair and a perpetual tan like Phil Harris, and Miss Overgaard as Mario’s assistant chef, who would make me turkey sandwiches on white toast and I would smear it with ketchup and crunch while we sit in a booth just the two of us and she would tell me dramatic stories, with a nod for emphasis and her jaw waggling (so she looked like Winston Churchill), while we heard Mario’s voice pealing in the kitchen over the rattle of pots and pans.

And after we closed by midnight or later, Mario would be the old school gentleman again and drive many of the staff home: the cooks and waitresses and bus boys, including Louis the dishwasher, with the softest voice in the world and the gold tooth, who eventually became Mario’s alter ego.

Then when the nightly rounds were over, and we were all deposited safely home, Mario and Helen would get back to their house on Third Avenue, the one next to the Irish store, which played Irish music during the day: that was the house that during Mario’s bachelor days would have linoleum tiles polished so slick (and he insisted you take your shoes off) that you could easily go flying.

Only Mario being Mario, he had a line of slippers thoughtfully waiting that you could slip into—of all sizes and genders.

I will always remember him as the most relentlessly curious man in the world, one who would sit hunched with my dad over the kitchen table, learning all about the Greek history he had missed, always beat me at chess on the chessboard played with ivory knights, and who would always listen with his hawk eyes riveted when you told him something, even if you were just a kid.

Although we lost touch in later years, we did see each other for family occasions, and the last time I visited him (now in his 80’s and finally retired), he was reading book after book and wearing square reading glasses and telling me all about the last one he read, by someone named Tolstoy. I thought it was the famous Leo Tolstoy, who wrote War and Peace, so I told him about Leo Tolstoy, one of my literary idols, but it turned out to be the wrong Tolstoy.

Only Mario didn’t care, he listened amiably and learned something new and was glad for the company, and he looked like a man at peace with himself, his relentless drive abated, and grateful for the family he had around him and he could now sit back and enjoy: my sister Helen, who had always stood by him heroically, his children Nick, Eva, Kally, Kosta, and his grandchildren Peter, Elle and Jack.

He was demanding of himself, and demanding of all of us, but that’s what had made him a classic immigrant success story. And yet inside he was still the little boy of the refugee camps, who would give you his heart if you gave him yours: the most incredibly alive and vital man I knew.

I will always miss him.

0 comments