Iast month’s issue focused on our quick trip to Constantinople, the quintessential “hameni patrida [lost homeland].” The few thousand Greeks who hang on in Turkey’s largest city are locals, with roots in the city for over 25 centuries, far longer than the Turks who progressively expelled them. Venice, as we discussed a few months ago, in my opinion was the first true Diaspora community, as Greeks (or Byzantines) immigrated there, congregated around the Orthodox church, and established institutions and community life that would be familiar to any Greek-American or Greek-Australian.

Greece is a successor state to the Byzantine Empire and like all resurrections of past polities, it is in some ways inaccurate. It lacks the frontiers of the Byzantine Empire that it tried to recreate with the ill-fated Megali Idea (Great Idea). As such, large populations affiliated with Greece, or at least with Byzantium, remained outside the frontiers of the Modern Greek state. At the same time, Greece developed over five centuries a considerable and influential Diaspora. Finally, Greece is not the only successor to Byzantium and other states vie for the souls and the allegiance of these post-Byzantine populations.

Certainly Greek settlement in North and South America, Australia and Central and Northern Europe are clear examples of Diaspora communities, which Greeks founded after immigrating to these distant lands. The Greeks arrived in an alien environment, adjusted as needed to become successful and assimilated to varying degrees. I would also argue that the Greeks of Marseilles in France and Alexandria in Egypt are a Diaspora, even though the Ancient Greeks established their respective cities. The Greeks’ emigration to these cities was recent and motivated by economic factors, rather than a continuous community from antiquity. Closer to the Byzantine heartland, the Balkan and Asia Minor Peninsulas, the question is more difficult and as I have found through both research and from personal experience, it is always more controversial.

The Greek-speaking communities of Southern Italy are clear ethno-linguistic remnants of communities who lived in this part of Italy since antiquity. The Byzantine Empire held sway here until the mid eleventh century and these Greek-speaking Orthodox communities remained, though Roman Catholicism eventually took over ecclesiastical authority by the 1400s. These small, insular communities did not have a strong link to Greece and though Greeks fleeing Ottoman rule did settle in these lands, the local identity reigned supreme. Today, the nine Greek-speaking villages of La Grecia Salentina (a small region in the middle of the Italian heel) maintain several cultural associations emphasizing their music in the local dialect, Griko, a grammatically simpler version of Greek written in the Latin (which itself is an original Greek) alphabet with a fair mixture of Italian words, anachronistic terms and a complete absence of the Turkish expressions that spice modern Greek. When I visited, in 2000, I found that most local people I talked to could carry a simple conversation in Griko and in a few villages, schools teach the language. They view the Greeks in Greece as “cousins” but have no sense of belonging to a Greek nation. They are Roman Catholic Italians, though some locals have converted to Orthodoxy out of cultural discovery, but this is the exception that proves the rule.

When I lived in Bulgaria in the summer of 1994, I saw reminders of Greece everywhere. It makes sense, as Greece and Bulgaria were the heartlands of both the Byzantine and the Ottoman realms and the border between the two countries, in Macedonia and Thrace, really represents a cease-fire line between the Greeks and the Bulgarians, rather than a true ethnic frontier. As a Bulgarian friend once told me, “between us and you (Greeks) there is no border, that’s part of the problem.” He was more right than he knew, the Greek and Bulgarian ethnicities and identities, both bound in Byzantine Orthodoxy, are thoroughly mixed together. After the Balkan Wars and World War I, Greece and Bulgaria conducted a voluntary population exchange and about 60,000 people went each way. The remaining Greeks in Bulgaria, or Bulgarians in Greece, generally assimilated into their surroundings. It was not difficult, as they were among co-religionists and the only real change was linguistic and state identity, which was still quite fluid. Time and again on the Black Sea coast or in the City of Plovdiv, known to Greeks as Philipoupolis, local Bulgarians would tell me, often as not in decent Greek, about their Greek grandparents.

The whole Black Sea littoral is a veritable necropolis of Hellenism, with still living remnants of “Romiosini” scattered all along the coasts. City names, Sozopol in Bulgaria, Sevastopol in Ukraine, and Trebizond in Turkey, to name just a few, all bear witness to their lost custodians. In 1814, three Greek merchants in Odessa, Ukraine’s second largest city and principal port, established the “Filike Etairia,” the secret organization dedicated to the liberation of Greece. Even a century ago, Greek was a key commercial language in the Black Sea basin. Today, In Bulgaria and Romania, Greeks have mostly assimilated or emigrated to Greece. The same is true in Russia, the Ukraine, and Georgia, though all three countries still possess distinctly ethnic Greek villages, clinging on to their identity with the general support of their current governments. Stalin forcibly uprooted many of these communities to Central Asia and several hundred thousand have immigrated to Greece in the past twenty years. When I served in the Greek military a few years ago, a good ten percent of my unit was made up of Russian- or Ukrainian-born Greeks.

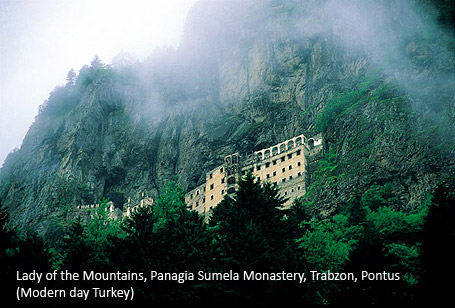

Many of these Black Sea Greeks are Pontic Greeks, originally from the Black Sea coast of Turkey. An exceptional lot, Pontic Greeks are in a sense a nation within the Greek nation. Their Diaspora is global, they remain distinctive within Greece though proud to be Greek and in their Black Sea homeland, in Georgia and in Ukraine, their language is still spoken. In Turkey, the Pontic speakers share a common ethnic descent, at least in part, with the Pontic Greeks, but they are Muslims. The Greek-Turkish population exchange basically divided the two nations by religion, to be Orthodox was to be Greek, to be Muslim was to be Turkish. This reflected the Turkish tradition of identifying their subjects by religion and was replicated by all of the successor states, whether Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, or Serbia. I am not going to speculate on whether these Pontic Muslims feel a kinship with their Orthodox kin, but they do live in Pontus, a quintessential Hammeni Patrida. At least, the ability to go to the villages above Trebizond today and to hear a form of Greek spoken in general parlance displays the profound reach of our Byzantine-Hellenic world. The Hammeni Patrida leaves its traces, even when the Orthodox religion so central to Hellenism is abandoned.

Hellenism outside the borders of Greece exists in many forms, whether as an established Diaspora community, the autochthonous remnants of a Hammeni Patrida, or the variously assimilated communities of these lands. These global Greeks reflect the tides, triumphs, and tragedies of our history, as well as the great diversity of Hellenism.