- FOKION AVGERINOS – DR. IKE: Athletic Director, Youth Mentor, and Healer

- American Hellenic Institute’s Golden Jubilee Celebration

- Leadership 100 Concludes 33rd Annual Conference in Naples, Florida

- Louie Psihoyos latest doc-series shocks the medical community The Oscar–winning director talks to NEO

- Meet Sam Vartholomeos: Greek-American actor

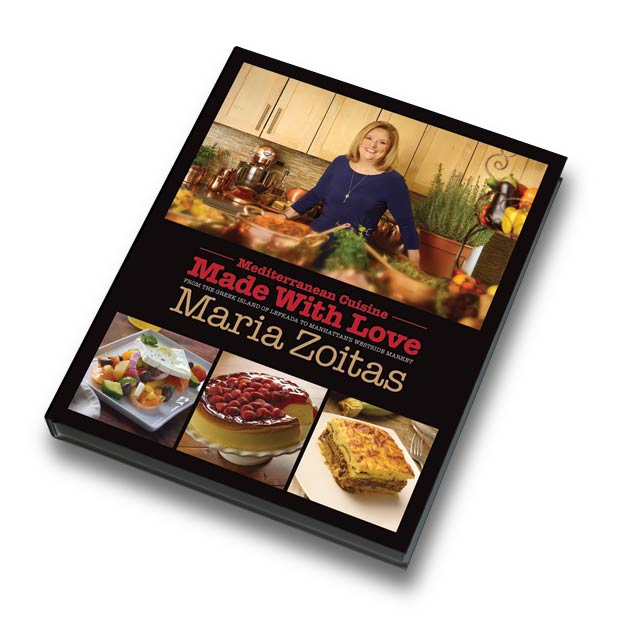

Maria Zoitas’ MADE WITH LOVE: The Ultimate Greek Cookbook from Lefkada to Manhattan

Maria Zoitas was a young bride when she first came to America and her husband John (who took her on romantic carriage rides during their honeymoon back in Greece) now plunged back to work at the grocery store he ran in Morningside Heights in Manhattan where he kept a Doberman for protection.

Maria Zoitas

“And I never saw him,” she says. “Except around the dinner table with his family because we lived with them. And I told him let’s go live by ourselves. And he said, you don’t even know how to cook fasolada. And I said who does the cooking now? My mother does the cooking, he said. Your mother only knows how to cook macaropita, I told him. I do all the cooking.”

From those humble beginnings, the family grocery store grew into a chain of gourmet markets called Westside Markets that have served Manhattan for years and also New Jersey.

From right: Maria’s son-in-law Demetri Belesis, who is a foundation of the business along with daughter Ermione; son George who works closely with his father as his right hand man; and the trusted store and department managers “Big” Jorge Arias, Nicko Glenis, Ian Joskowitz, John’s nephew Panagiotis Zoitas, Maria’s nephew Kostas Kavvadias, and Omesh Rangila

And Maria’s cooking has gone from the meals she made at home to a line of Maria’s Homemade cooking featured in every Westside Market and now compiled into a coffee-table cookbook that might be the definite guide to Greek cooking called MADE WITH LOVE: From the Greek Island of Lefkada to Manhattan’s Westside Markets.

“These recipes are my own inheritance as a little girl from my mother and grandmother and the generations of women in Greece who learned how to cook from the land,” she writes in her introduction. “They are the inheritance I want to leave for my own children and grandchildren—but also now to share with you.”

Maria & John Zoitas, George Zoitas, Ermione & Demetri Belesis, Anna Zoitas and grandson John

The list of the recipes is as exhaustive as the photographs are spectacular in what may become the ultimate Bible of Greek cooking.

“I pride myself that I never stopped growing as a cook,” says Maria. “So you’ll see recipes that I learned along the way in a whole lifetime of cooking, and also that I know my thousands of customers have liked: my customers are my extended family. Seeing people enjoy my food brings me great joy. And they always asked me, when are you going to write a cookbook? So here it is.”

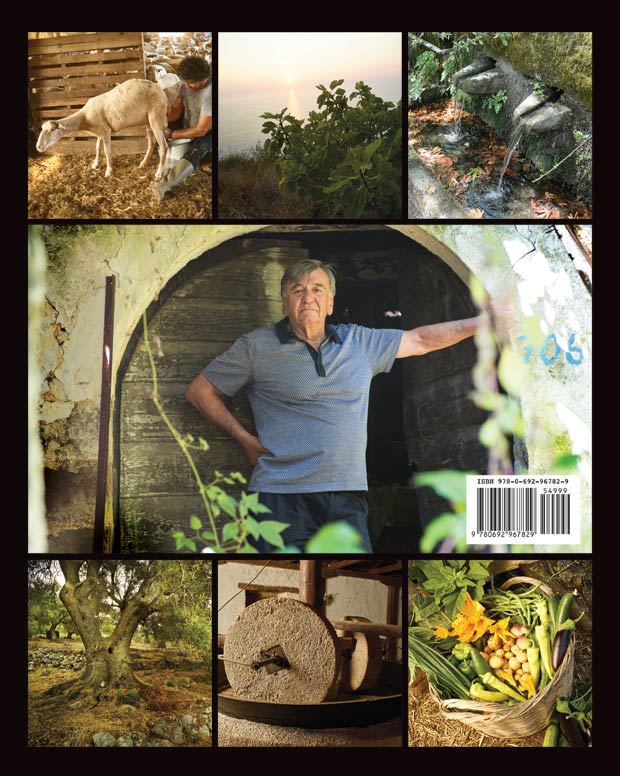

Besides the lifetime of recipes from her own life and the millennia of Greek cooking, the book is a loving tribute to her native Lefkada, named the White Island for its cliffs, which Byron recorded and Homer mentioned as the home of Odysseus. The island is also where Greece’s most flamboyant modern poet, Angelos Sikelianos, was born and where he tried to revive the ancient Delphic festivals, where the archaeologist of Troy Wilhelm Dorpfeld is buried in the midst of digging for royal tombs on the island, and where some churches are nearly a thousand years old and St. Paul preached.

It also has a Folklore Museum housing maps dating back to the 1600s, a Phonograph Museum with perhaps the most extensive and unique collection in the world, a Municipal Art Gallery with 28,000 titles mentioning Lefkada, and a marching band with a history of playing at the first modern Olympics, not to mention the island’s tradition of embroidery, which has been displayed all over the world.

“I also wanted to show Lefkada,” says Maria. “It has some of the purest waters in the world and every year thousands of sports lovers go there to surf and sail: in fact, it is among the top three windsurfing destination in the world.”

But the book is most of all a tribute to the Greek woman who did most of the cooking in Greek life, foremost among them Maria’s mother and grandmother, Efrosini and Efthimia Katopodis.

“Who were both phenomenal cooks and who always inspired me to enjoy and love the art of cooking by preparing the most exceptional and delicious meals for our family,” she says. “I love them and still miss them both very much.”

And it all began back in Dragano.

Dragano is the mountain village on Lefkada where Maria was born. Her husband was born on the other side of the mountain in the neighboring village of Roupakia, where her grandmother comes from.

“Before I got married,” she says, “I was the oldest daughter in a family where food was king and every meal was an occasion. Nobody ate until everybody was there to eat together, all eight of us: my father Angelo who loved food more than money, my mother Efrosini who gave the choicest portions to her kids (my sisters Effie and Hara and my brother Niko, who was the baby and the boy so he got the chicken liver and first choice of the loukoumi treat), and also my grandparents—including my grandfather Nicholas, who was a cop and generous with everything, including our food.”

It was a life without movies, without television, and no electricity, until 1972 (a car battery provided power when needed) and cooking and eating was the highlight of the day.

“And what we cooked was everything that grew around us,” she says. “Nothing was wasted: the must from the grape juice we used to make petimezi, a grape molasses, and a grape pudding often sprinkled with crushed nuts we call moustalevria (I still use petimezi in my recipes).”

The family also cultivated lemon trees and orange trees and lime trees, sowed wheat (by tossing it endlessly into the air to separate), grew lentils, but mostly they harvested olives to make olive oil—more than 100 barrels a year.

“Collecting olives was our livelihood, but it was a job I hated—you had to work in the cold, you had to scrounge in the gravel to collect the fallen olives, and it chapped my hands and chipped my nails and I hated it,” says Maria.

Fortunately, her mother took pity on her and let her cook instead to feed the family and the men who worked for them.

“The first ‘real’ meal I made was braised chicken, until I got my first real cookbook at 11, which I recently found again – a Greek cookbook circa 1961 called Cooking and Pastry “Asteros” – with my handwritten notes still attached for recipes like apples in syrup with walnuts,” she says. “And that’s when I also started making the so-called spoon sweets using seasonal fruit like figs, grapes and cherries soaked in syrup and usually served formally to guests—along with a glass of water to dunk your spoon and wash down the sweetness.”

But mostly she made the family’s everyday meals and they were strictly regimented.

“Our lunch was the most elaborate meal of the day and could be as sumptuous as my braised chicken, or stuffed tomatoes, or peppers, or eggplant with potatoes, or even rabbit stew,” she says. “And in my family everybody had seconds—usually more.”

Dinner was the lightest meal of the day, and in the summer it might be no more than some Kokkini soupa (tomato soup), or greens, or a slice of cheese pie, or a bread grilled in olive oil we called pyromada and then dipped in olive oil or wine for a treat called zoupa.

“Our family had some means (I wore leather shoes, a real luxury, when John had no shoes at all), so we might eat fish and meat several times a week from our own livestock, including rabbits, but otherwise it was a classic Mediterranean diet,” she says. “Everything cooked or prepared with olive oil, seasoned with herbs, and usually including a serving of vegetables cooked with the meal or as a side dish or as the meal itself. The ultimate vegetable dish was briami: a mélange of potatoes, zucchini, eggplant, onion, tomato and sometimes okra and bell peppers cooked in olive oil.”

Holidays, of course, were special and a Christmas meal

might start with avgolemono soup, yaprakia, also called lahanodolmades, (meat wrapped in cabbage leaves and baked) as a side dish or appetizer, lemon pork cooked with celery as a main course, and, of course, a table full of pastry and cookies: baklava, melomakorona (honey cookies), kourambiedes (shortbread cookies topped with confectionary sugar), karidopita (walnut cake with honey or syrup), ravani or pandespani (sponge cake made with mixed semolina flour and topped with honey) and the cookies or koulouria made with a dash of vanilla and brushed with egg yolk to give them a nice glaze.

“To break the fast on holidays and also to offer when visiting on birthdays and name days (and traditionally to mourners at memorial services), we would make hesperina, or as the locals call it sperna,” she says. “We would boil dried wheat berries and then add everything from raisins to pomegranates to blanched almonds and walnuts (for memorial services also topping it off with a coating of sugar and a pattern of Jordan almonds) and then bring it to church for evening services (why it’s called—hesperina—for evening vespers).”

Life could be sweet growing up on the island, watching the sun rise and fall from the sea, but it could also be hard for women.

“Even though I was a top student (I loved math and wanted to be a doctor) I had to drop out of school because I was the eldest daughter and had to learn how to be a homemaker,” says Maria. ‘Who’s going to marry you if you don’t know how to spread your filo?’ my mother would tell me. (Who’s going to marry you if you go to high school and all the boys look at you! my father would tell me.)”

And then John came into her life.

His life was an odyssey unto itself.

His father wanted to make him a priest, not for the meager salary but for the tips he would collect at weddings and funerals. Then he wanted to make him a cop, but John was too short and he had already served in the Army. So since the family was very poor, John was still a boy when he had to leave home to find work, and then only a teen where he traveled from Germany to Australia and then America, where he worked first at a coffee shop in New York City (Hey, young man, he says they called him), then at a grocery store he liked better; until he bought his own store with the little money he had, and then another (working with his brothers), which he slept in to guard it and where supposedly the bodies fell from windows because the neighborhood was so rough and he kept two Dobermans to protect him.

“That’s when he came to Greece to find a bride to share his ‘life,’” says Maria with a rueful smile about her arrival in America. “Because I was suddenly very alone here: we lived with John’s extended family (nine people brought over by their bachelor uncle Andreas) and we lived with all the other Greeks in Astoria, but I missed my own family, and John was never home.”

To keep herself busy she kept up with her cooking.

“I cooked for the whole family and waited for them to come home,” she says. “That’s when I learned how to roast turkey and make stuffing from my father-in-law who learned it from Andreas who was a chef all his life in diners. The first Thanksgiving with the turkey and the stuffing made a big impression on me. (I also learned the mysteries of adding egg to my filo so it wouldn’t stick.)”

After about a year of staying home, she went to the store to help her husband, only she couldn’t speak English, except for a few choice words.

“I worked the register and when the customers got rough I would tell them, ‘Aw, shut up, stupid,’” she laughs.

She made their lunch an elaborate affair: lemon chicken, chicken with peppers, macaroni with meat sauce, fried eggplant in tomato sauce—hearty meals, which John quickly got used to—and which his partner at the store, Christos, would eat by the bowl.

But then she got pregnant and stayed home to raise her kids, until her kids went to school, and she decided that what the stores really needed was cheesecake—home-made cheesecake.

“It was a classic American dessert and everybody loved it,” she says.

But John was an old produce man.

“I’d rather sell a box of bananas,” he told her.

So she got her brother Nick, also working at the store now, to bring her cheesecake to the store, only when she went down to the store one day herself she saw all her cheesecakes stacked up in the fridge.

“I’d still rather sell a box of bananas,” her husband insisted.

But she got him to display it, and it sold, and then she tried spanakopita and falafel and ready-to-eat hot meals, and when they sold, John, the smart businessman, finally relented “and gave us some space in the basement to cook—not much space, enough for a mixer and a hot plate, and together with Mike Katopodis (also from Lefkada) we got started on Maria’s Homemade.”

“We were so successful with Maria’s Homemade that John gave us more and more space for our prepared and hot foods, until our kitchen soon ran practically the length of each of our stores and our staff grew from just Mike and me and our mixer and hot plate to literally dozens of people and then the hundreds we now employ working in shifts round-the-clock.”

Today the stores make over 600 fresh items every day, ranging from 20 kinds of couscous, 30 kinds of soup, an endless variety of salads you can buy packaged or make yourself, over 450 types of cheese to choose from, and a complete menu of hot meals from rotisserie chicken with assorted seasonings (hundreds sold every day) to wild poached Atlantic salmon with lemon dill sauce.

“And I’m a stickler for using only the freshest ingredients,” she says. “Just like the herbs I picked back in the mountains of Dragano and I still use in my own home cooking today. Only now I cook for most of Manhattan, too.”

Maria still supervises her kitchens, and John still designs the displays with paper and pencil, but now their kids oversee the stores: her son George with her son-in-law Dimitri Beleses (who both went to business school), her daughter Anna who also went to business school and worked at the store (and sold her own brand of olive oil), and their daughter Ermione, who later became a teacher.

“We’re a family and our employees are family, too,” says Maria.

And so are her customers, who had been clamoring for her cookbook for years. So after a two-year effort, which involved not only compiling and testing her recipes to make them accessible to everyone, but also visiting Lefkada to do even more research and take the breathtaking photographs, MADE WITH LOVE was finally published this Fall and is now available on Amazon and other outlets and always at the stores.

“This is my legacy,” says Maria. “The legacy to my family to show them my life and work, but also to show them where I came from and what life was like on an island like Lefkada, which is still beautiful, always beautiful, and which is still my second home.”

The book makes a spectacular holiday gift and all proceeds will go to charity.

0 comments