- FOKION AVGERINOS – DR. IKE: Athletic Director, Youth Mentor, and Healer

- American Hellenic Institute’s Golden Jubilee Celebration

- Leadership 100 Concludes 33rd Annual Conference in Naples, Florida

- Louie Psihoyos latest doc-series shocks the medical community The Oscar–winning director talks to NEO

- Meet Sam Vartholomeos: Greek-American actor

Ghosts of Communist Greece in Serbia

Alexander Billinis

In spite of a very different climate, in Serbia you are really never far from Greece. The culture, the history, the religion, and even the DNA are often eerily similar. Greek-Serbian interaction goes back from the Byzantine era to the present day multitude of Greek investors, students, and expats (like me), and as I have found living here, in Serbia’s northwestern Vojvodina province, the Ghosts of Communist Greece are all around us.

Until recently we lived in Sombor, a lovely city clearly showing its heritage as a key center in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. Its population has always been a mosaic of Serbs, Hungarians, Croats, and other nationalities. The architecture and homes, including ours, would not look out of place in Austria and Germany. Indeed, the villages surrounding Sombor were once full of Germans speaking a Schwabian dialect, until the post-World War II era.

Postwar Yugoslavia, like other East European states, decided to solve their “German Question” once and for all by the wholesale eviction of their German citizens. These empty villages, with their solid, well maintained houses and farms, needed to be repopulated. Serbs from mountainous areas of Yugoslavia moved in, but two former German villages in the area hosted Greek Civil War refugees.

The first one was Bulkes (currently known as Maglic), a former German village emptied of its inhabitants in late 1944. It was not empty for long, as several thousand Greeks moved in, Communist refugees who refused to recognize the Varkiza Ceasefire Agreement in 1945, after the December 1944 Greek Civil War. For four years thereafter, Bulkes functioned as a mini-Greece within Yugoslavia, complete with its own Greek-language schools, infrastructure, media, and even its own currency—Bulkes Dinar, valid only within the community’s limits. It was called the “Seventh Republic of Yugoslavia.”

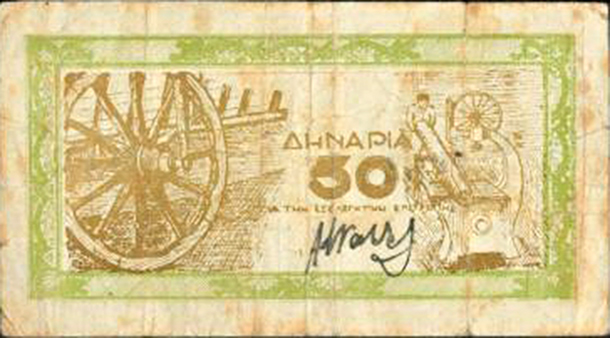

Bulkes Dinar was the currency used 1945-49 when the village was an autonomous Greek community within Yugoslavia, with its own government. Photo furnished by Orfeas Skutelis, whose father was born in Bulkes.

Bulkes primarily functioned as a rear camp for the Greek Communist forces, but it also had a community life of its own. In typical Greek fashion, the Greeks broke into factions, and had their own mini-civil war within the town limits, what one Civil War era refugee described to me as a “St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre—lasting three days.” This internal conflict and the impending defeat of the Greek Communist guerilla forces meant that Bulkes had reached its expiration date, and as quickly as the community was established, it was disbanded; some of its inhabitants stayed in Yugoslavia, and the rest were settled elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc and then scattered, in typical Greek fashion, to the four winds.

Further north, just a bike ride away from where we live in Sombor, lies the village of Gakovo. Here refugees arrived in the latter stages of the Greek Civil War, and the majority of these were Slav Macedonians rather than Greeks. Unlike Bulkes, the refugees here had no autonomous status but rather settled in recently vacated German houses and were put to work on farmland or in other activities sorely needed for reconstruction of war-ravaged Yugoslavia. Here too schools were established (Slavic and Greek) but the community lacked any autonomous status similar to Bulkes.

Tito’s Yugoslavia had supported the Greek Communists in their quest both to seize power in Greece, and to assist Slavophones in Greece to amputate parts of Greek Macedonia. Once the Greek government forces gained the upper hand, and, crucially, Tito and Stalin had a falling out, the Greek Communists in Bulkes, Gakovo, and those fighting in the mountains of Macedonia and Epirus became a potential Trojan Horse against Tito’s independent Communist regime. Ever the pragmatist and survivor Tito abandoned the Greek Communists and shut down their mini-Republic in Serbia. Most former residents of Bulkes or Gakovo were shipped to Stalinist controlled countries, such as Hungary, Czechoslovakia, or the Soviet Union. By the early 1950s, with a Cold War in full swing, Yugoslavia re-established the traditional close ties between Athens and Belgrade, Tito and King Paul enjoyed the sun together in Corfu in 1954, and the whole “late unpleasantness” was forgotten officially.

The Bulkes Train Station, arrival and dispatch point for Greeks in the secret community. Photo by Georgios Makkas, grandson of the famous Greek playwright and author Alexis Parnis, who as a Greek Communist guerilla spent a good deal of time in Bulkes.

Today, most of what we can learn about Bulkes and Gakovo comes from the witnesses themselves; the archives are generally off limits or, as I found in Sombor, devoid of information. This is no accident but rather a policy of silence. Those former residents of these “Greek villages” whom I encountered, either Greek or Slav, generally have been willing to relate their experiences as child refugees but they lack details; their elders either did not survive the Civil War, of if they did, they tended to be rather quiet as to what they endured.

Gakovo and Maglic (the new name for Bulkes) today are like so many former German villages in Serbia’s Vojvodina province. The vast majority of today’s inhabitants are Serbs, generally from parts of Croatia and Bosnia (including many recent refugees from the wars in the ‘90s). They occupy the same German homes the earlier Greek refugees lived in, and in both towns a decaying German Catholic or Protestant Church is a stone’s throw from a new Serbian Orthodox Church, built in Serbo-Byzantine style the Greek refugees would have known well.

0 comments