- FOKION AVGERINOS – DR. IKE: Athletic Director, Youth Mentor, and Healer

- American Hellenic Institute’s Golden Jubilee Celebration

- Leadership 100 Concludes 33rd Annual Conference in Naples, Florida

- Louie Psihoyos latest doc-series shocks the medical community The Oscar–winning director talks to NEO

- Meet Sam Vartholomeos: Greek-American actor

Papou O Polemistis

Papou Petro and Yiayia Pota were coming from Florida for Christmas and this time they were bringing Propapou Herakles—Hercules—even though Propapou Hercules looked more like a Hobbit.

And Mom said he was staying with George in Petro’s bed because Petro was celebrating Christmas with his girlfriend’s family in Connecticut.

“He’s staying in my room?” said George.

“Yes,” said Marina, his sister. She didn’t have to sleep with anybody in her room because Papou and Yiayia were going to sleep in the fold-out couch in the basement—where George kept all his video games and the ping pong table that opened up into a pool table and foosball table and where he kept his comic books and Dad had his stereo equipment and his plasma TV and Papou and Yiayia were probably going to be watching Aktina TV all day!

This wasn’t fair!

This was going to be the worst Christmas.

“Oh, suck it up,” said Marina.

Only she didn’t have to sleep with anybody in her room!

“Not fair,” said George to his mother in the kitchen, where she was baking already. And she kept baking and ignoring George. “Aren’t you supposed to be baking with Yiayia?” he said to her.

“She has arthritis,” she said to him and curled a koulouri.

“Papou likes to make the tsoureki,” he said to her.

“He can’t see well,” she said to him. “And he has arthritis.”

It was pretty bad getting old: you couldn’t do anything except wear a sweater and slippers and sit and watch TV.

And old people always liked cartoons: like the Flintstones.

And I Love Lucy: Propyiayia Frosini always made George find I Love Lucy on TV and then sit there knitting soda caps into hot plates and laughing at Lucy, even though she couldn’t understand what she said: “What did she say, Georgaki mou?” she would ask George. “Na ei mourli,” she would chuckle.

Proyiayia Frosini was very nice: and she smelled like the butter that she heated and whisked as a glaze on her koulourakia. George liked her koulourakia the best because they were golden-brown and they tasted like vanilla. Mom made her koulourakia real yellow so to George they tasted like lemon.

“No, they don’t,” said Marina.

“Yes, they do,” said George, because he missed Proyiayia sometimes.

When Yiayia Pota came to New York she went shopping at Macy’s.

“Is your room clean?” George’s mother said to him now in the kitchen.

“Yes,” he said, trying to get a nibble of the amigdalota which Dad had bought at the Greek store and were still in the box with the string, but which nobody was allowed to eat because it was for Papou and Yiayia and Propapou Hercules when they came, even though they weren’t supposed to eat them, either, because they all had diabetes and high cholesterol, but Mom liked to get Dad to buy them and put them on the bureau with the mirror, because it was traditional—except nobody was supposed to eat them!

“Make sure your room is clean because we don’t want Papou Herakles to trip and fall and break a hip,” said Mom, rolling some koulouri dough and brushing back her hair with her forearm and checking in the oven for the koulouria that were already baking—and that’s when George stole an amigdaloto! “Make sure you put your stuff away,” said Mom, coming back from the oven and brushing back her hair with her forearm again and taking off her oven mitt.

“Fine,” said George, teeth clenched, because he had the amigdaloto in his mouth, and the rest of it in his hand. ”How old is Papou Hercules, anyway?”

“Ninety-one,” Mom said.

“How could anybody be ninety-one?” said George.

“Nineteen-Twenty-Eight,” said Mom, who knew everybody’s birthday, even if they were old: she had all of the birthdays listed in her iPhone.

“That’s crazy,” said George.

“Not crazy,” said Mom, getting flour on her mouth, so now it looked like she had white whiskers like Colonel Sanders. “And Papou Herakles is a hero.”

Papou Hercules was a hero?

Since when?

He was practically shorter than George.

And all he did was smile and sleep: he even smiled in his sleep.

“Before you clean your room Dad wants you to go the garage and help him there,” said Mom, blowing up on her bangs.

So George walked down the stairs to the garage—past Marina in the living room polishing the end tables with Pledge like she was drawing on them, because Marina was very artistic, and when she polished anything it always looked like she was finger painting.

“Aren’t you finished yet?” George told her.

“Get lost,” she said to him and stuck out her tongue and went on polishing the end tables like she was finger painting.

Dad was in the garage organizing all his tools, because Papou Petro always came into the garage when they visited and borrowed Dad’s tools to do repairs around the house.

“How come he always does that?” George asked his dad.

“Because he knows how to do it,” said Dad, who was a chemist and worked for Monsanto.

“How come he knows how to do it?” said George.

“Because he used to do roofs,” said Dad.

“What’d he do with them?” said George.

“Fix them,” said his Dad. “He used to climb roofs like a monkey.”

George couldn’t imagine his papou climbing roofs like a monkey. And he couldn’t imagine his yiayia sewing wedding dresses for people—which is what she used to do—or maybe George could imagine her doing that because she always went shopping at Macy’s.

“So what did Papou Hercules do?” said George.

Papou Hercules lived with Papou and Yiayia, until Yiayia Frosini died, and then he got sick and needed a nurse, so they moved him to a home that looked like a resort, and it had palm trees and flamingos floating on the water, because Papou Hercules liked palm trees and water and flamingos.

“Papou Herakles was a sailor,” said Dad, rattling around the tools and making them neat.

“Really?” said George.

“You know the sextant I have on my shelf?” said Dad.

“Yeah,” said George.

“That used to belong to Papou Herakles when he used to sail the Seven Seas and from Greece to Spain to Rotterdam to Africa,” said Dad.

“Really?” said George.

“And when he was a kid he used to climb up on the rigging,” said Dad.

“What rigging?” said George.

“On the kaikia on Chios when he was a kid,” said Dad. “The kaikia that went fishing.”

Really? thought George.

“And I showed you the stick,” said Dad.

“What stick?” thought George.

“The stick with the hair on it,” said Dad. “That’s giraffe hair and it was given to Papou Herakles by an African chief.”

No way!

“And all the other stuff in the sea chest in the attic,” said Dad, poking through the little drawer of screws with his finger.

“What sea chest?” said George.

“The one with the gold buckles in the attic,” said Dad. “You got all sorts of stuff in it that belonged to Papou Herakles.”

Wow, thought George.

He couldn’t wait to finish cleaning up the garage with Dad, because then he ran into the house, stole another amigdaloto from the kitchen, then ran upstairs to the coat closet that had the little ladder you had to pull down to get to the attic, and went up the ladder and into the attic, where the air swirled with dust, and the clothes all smelled—and there in the corner of the attic was the sea chest with the gold buckles that nobody ever paid attention to.

Only George stared at it now in wonder.

“Wow…” he said, as he stumbled over Mom’s cookbooks and Dad’s test tubes, until he got to the sea chest and stood over it and he could practically smell the sea now. “Wow…” he said.

He dropped to his knees and felt all the rivets on the box: they were very big, like chick peas. And then he felt the buckles: they were gold, and very big, like the belt buckles the wrestlers wore in WWE.

“Wow…” said George.

The buckles were unlocked and George flipped one open, then flipped another one open—and he flipped all of them open—then stood up and heaved the top open and it creaked and fell back with a crash that made the whole attic shake!

But then it smelled great—it smelled like musty old things.

George dropped to his knees and stared inside.

“Wow…” he said.

He picked up a walking stick that had carvings on it.

And an old gun belt with white pouches and white string.

And a helmet—a soldier’s helmet—only almost flat like a pan, but with netting on it.

And boots—high boots with laces on them and round toes.

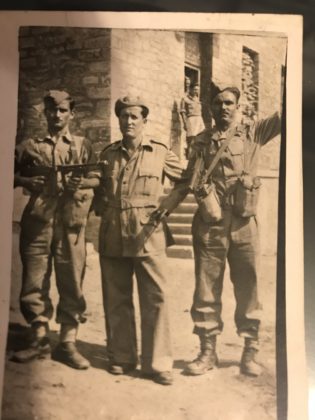

And a brown picture of three soldiers in uniform: one of them standing and holding a rifle, another one holding a rifle and wearing a gunbelt, and an officer in the middle wearing a beret and with his leg cocked who looked like Papou Hercules.

Wow, thought George.

“George—where are you?!” Mom yelled to him from below. “Papou and Yiayia are here with Papou Herakles!”

Wow! thought George, bounding to his feet.

He ran to the window, saw Papou and Yiayia’s Buick pulling into the driveway, and he clambered down the little ladder again, and tumbled down the stairs to the living room, and out the door, and down the driveway, just as Papou Petro got out of the Buick and gave him a big hug with his hairy arms, because he wasn’t wearing a jacket even though it was very cold, and he knocked him on the head with his gold ring and gold watch when he hugged him, and then Yiayia Pota gave him all these smacking kisses all over his head and cheeks, and then everybody tried to get Propapou Hercules out of the car—practically lifting him up by his arms and legs like a string puppet.

“Only be careful with Papou…” said Mom, still wearing her kitchen apron and holding a spoon.

“I got him,” said Dad, lifting Papou’s one leg.

“I got him,” said Papou Petro, lifting Papou Hercules’ other leg.

And then they practically carried him into the house, with Papou Hercules hanging in the middle like a string puppet.

This was the hero and the sailor who had sailed the Seven Seas? thought George.

Everybody sat in the kitchen and cracked nuts and ate them, while Mom cooked with Yiayia, and Marina sprinkled the powder on the kourambiedes like she was making snowballs, and Papou Hercules sat in the den in Dad’s old recliner, that used to be Papou Petro’s old recliner, and he was cranked back with his slippered feet sticking up and he was sleeping—with a smile on his face and his little hands folded on his lap, with his wedding ring on his middle finger.

Papou was talking about holiday traffic and how he had avoided the holiday traffic, Dad was helping Mom stir the honey for her melomakarona, and Yiayia was baking almonds in the oven and talking about Kyria Sousou, who used to be their neighbor in Astoria, but now lived in Port St. Lucie with them, and how many kids she had married off, and how many grandkids she had married off, and what jobs they had, and Kyria Sousou’s blood pressure, while Marina kept adding more powdered sugar to the kourambiedes, and Mom and Dad kept stirring the honey, so George walked away and walked into the den and dropped down on the carpet and stared up at the bottom of Papou Hercules’ slippers sticking up like elf feet.

Only then Papou Hercules popped one eye open—and it looked at George—and it winked at him!

And then Papou gestured George near, and when George waddled over on his knees, Papou Hercules tickled his ear and patted his cheek with a hand that smelled like nutmeg.

“Tsou, tsou,” he said to him, spitting to ward off the evil spirits.

George smiled politely, Papou Hercules winked at him again.

And then George couldn’t help himself—

“—Were you really a sailor and a soldier and use a sextant and wear a flat helmet with netting on it and a white belt and really get a stick with hair on it from an African chief and climb up on a kaiki and go to Rotterdam and Spain and was that you in the brown picture with the soldiers with the guns and was that you in the beret?” he said all in a rush.

And he waited with his mouth open.

And Papou Hercules nodded and smiled, before he took George’s fingers and caressed them one-by-one.

“Yiayia—“ he said “—she was from Africa!”

He waved his hand behind his ear to show how far that was.

And he nodded to confirm it.

And he closed his eyes to confirm it.

And then he opened them again.

“South—Africa!” he said. “Greek peoples live there!”

“Wow,” said George. “Why?”

“Greek peoples live everywhere!” said Papou, popping his eyes open. And then half closing them again and smiling. “Yiayia live there. I come on a ship in Saldanha Bay, South Africa, and Yiayia live there—on a strema!—and she ride a horse!”

And he pretended he was galloping–in Dad’s old recliner.

“Yiayia come to the ship to buy goods!” said Papou Hercules. “And she come off her horse, and I come off my ship, and we see each other—and I stay then in Africa!”

Papou Hercules smiled, George smiled.

“So you saw elephants?” George said.

“I see giraffes!” said Papou Hercules. “African chief was my friend!”

“Really?” said George. “So he gave you the stick with the giraffe hair?”

Papou Hercules waved his hand behind his ear again like that was taken for granted among friends.

And then he shook his head.

And then he cupped his hands on his lap.

“But then came the war!” he said, waving his cupped hands. “The Germans come!” he said and he cocked a finger suddenly and pretended he was shooting a gun. “So I fight!”

“Where?” said George. “Like in Africa?”

“In Greece!” said Papou vehemently. “I take the submarine!”

What submarine?!

“But the Italians almost sink it!” said Papou. “Italian heavy cruiser—Gorizia!”

Wow!

“I go to Greece to join my unit!” said Papou, slapping his chest under his mustard-yellow sweater. “The Petromichalis Light Tank Infantry!”

“So you had a tank?!” said George.

“British! The Churchill Crocodile!” said Papou.

“Why’d they call it the Crocodile?” asked George.

“Because it had big teeth!” said Papou, mashing his dentures.

“So you fought the Germans in your tank and everything?” said George. “That was you in the picture with the beret?”

“And my men!” said Papou. “We fight the Germans! We fight the Italians! We fight the Albanians! We fight everybody!”

Yiayia Pota suddenly came in with her slippers clacking and said Papou Hercules had to use the bathroom now. She yanked down the footrest and Papou sat there waiting for her to get him up. Then he got up and waited for Yiayia Pota to bring over his walker.

But first he reached into his pocket and he gave George something–and George stared at the big yellow tooth in his hand.

“Tiger tooth,” Papou Hercules whispered to him, before Yiayia Pota made him use his walker and it clicked with every step as Papou Hercules walked to the bathroom.

0 comments