This condensed interview with Michael Cacoyannis, famed stage and screen director and producer, who died in July of last year, was conducted in New York in October, 2000 and is reprinted here in memory of the Cyprus-born movie maestro.

by Vicki James Yiannias

“Come up at 3:00”, said Michael Cacoyannis, agreeing to an interview at the Park Lane Hotel in Manhattan on November 5, 2000, “but it can’t be very long, because frankly, I’m bushed”.

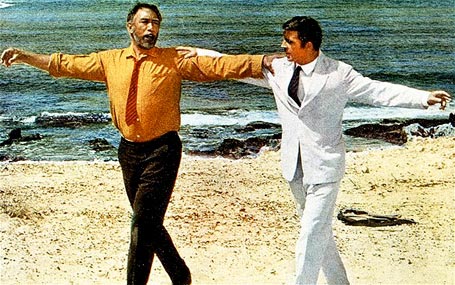

Understandably so. Mr. Cacoyannis, whose 3-Oscar winning 1964 box office hit “Zorba the Greek” –just one of his masterpireces–thrust him into the all-international fame was in the United States for a string of events that began on October 23 with the all-Theodorakis concert at Lincoln Center, celebrating the 75th birthday of his long-time friend and artistic collaborator, and stretched to November 14, during which time Cacoyannis accepted Hellenic Public Radio Cosmos FM’s Phidippides Award and attended the special opening of the new Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation at the Olympic Towers as well as Patriarch Bartholomew’s blessing of the new Jaharis Galleries for Byzantine Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Surpassing any of these events in importance, however, said Cacoyannis, was the opportunity to see his “many close and beloved New York friends”.

In spite of being “bushed”, Mr. Cacoyannis was generous with his time, giving an interview that turned out to be substantially longer than short--and punctuated by his puckish sense of humor.

Dapper, elegant, and energetic, Mr. Cacoyannis delayed starting the interview until he found a vase for the interviewer’s token gift of a long-stemmed red rose.

VJY: Some of the questions I’ d like to ask aren’t the usual, expected questions for an interview. I hope you don’t mind.

MC: On the contrary, I hope they won’t be. Interviews are all the same. Everyone asks the same questions… just don’t ask me what my favorite movie is.

VJY: I wouldn’t think of it. Your humor in “Windfall In Athens“ is exquisitely, whimsically funny; and although I realize that “The Day The Fish Came Out” is a film with a dead-serious prophetic message about atomic radiation, it was the most hilarious movie ‘I've ever seen.

MC: You thought it was funny? Yes, yes it was… I guess you wouldn’t say that about “A Girl In Black”. You’re probably the only person that liked “The Day The Fish Came Out”; it wasn’t appreciated by the American public. They didn’t like their political leaders ridiculed.

VJY: If that was so, it was just ahead of its time. Today, much fun is made of political figures in movies.

MC: Yes, but it wasn’t only that; there was also the circumstance of “The Day “The Fish Came Out” coming after “Dr. Strangelove”. There were thoughts that The Day The Fish Came Out” was ‘second best’.

VJY: Have you ever pursued an art not associated with the theatre?

MC: Yes, I have painted. Twice in life I have painted like crazy, shutting myself up for 16 days at a time. Obviously I would have become a painter.

TGA: Has anyone seen your paintings?

MC: It can’t be avoided...the walls of my Paris apartment are covered with them.

TGA: What medium did you paint in?

MC: I was never trained…I use everything -- gauche, watercolor, oils -- but not all together, of course.

VJY: When you were growing up in Limassol, Cyprus, until age 17, were you creatively inspired by the mingling of cultures on the island?

MC: No, the fact of their coexistence was un-influential in those terms. My father got along with the British and the Turkish residents; there was no prejudice. And then, of course, it was predetermined that I would study law in London...I didn’t have a choice in the matter.

VJY: Did your study of law influence your work as a director in any way?

MC: Absolutely not! Even today I can’t stand to look at a contract or any document of that sort. But by the time I decided to leave the law in London and move to Greece, I was already an adult living far away from Cyprus. It was my own decision by then.

VJY: Do you still have your family house in Limassol?

MC: Yes, but I also have a house on the beach halfway between Paphos and Limassol where I spend a lot of time. I don’t get dressed for weeks at a time.

VJY: Are you active in the Cyprus cause?

MC: Yes, I’m doing what I can. But I don’t feel very positive about President Ecevit since he was the head of Turkey when Turkey invaded Cyprus...so can he be trusted?

VJY: I read that you said your teacher in London, a 70 year old Middle European refugee, guided you “through a challenging trip of self-discovery”, teaching you “the dynamics of human expression, physical as well as spiritual, that elevate life into art” .How did she effect that?

MC: She taught me that art is a projection of life and to study life, to integrate it into my work. Now people play with machines, computers...but computers, too, can be extraordinary things, producing extraordinary results of a totally different type. I’m a believer in personal talent. The individual must do what he has to, so he can breathe.

I also believe that at some point there will be a creative counter- revolution.

VJY: How do you choose your actresses?

MC: I didn’t choose them all in the same way; there were different reasons for each choice. Of course, I choose them because I admire their work, but also from knowing them, knowing their psychology; that extends into how I perceive that person as an artist. I was friends with many of my actors before they were in my films. And my relationship with them doesn’t end just because a film is finished…it is continuous...it exists before and continues after the film is finished.

VJY: How did you choose Melina Mercouri for “Stella”?

MC: I knew her socially in Athens for a long time and had seen her act before I cast her as Stella. I knew she was a very talented actress. She hadn’t been in a movie. She interested me because her looks had been criticized...her mouth, her articulation…she had irregularities, exaggerated features.

VJY: And Tatyana Papamoschou for the role of Iphigenia, in your 1976 “Iphigenia”?

MC: I met her on an airplane, actually. She was only twelve years old. Her father was an Olympic Airways pilot. She was sitting in first class with her mother and I could only see the back of her head. I kept repeating to myself over and over, “Please let it be a girl”. Then she stood up to go to the bathroom, and when she walked back to her seat I saw her face...saw that she was a girl, it was fantastic. She was perfect. I had wanted a faun, and she was that. She worked very hard -- I drilled her mercilessly for four or five months. She was so modest that she didn’t tell her friends that she was rehearsing to be in a movie. When “Iphigenia” opened, and her friends saw her, the telephone didn’t stop ringing...”why didn’t you tell us you were in a movie” and so on. The experience influenced her to pursue acting. She still acts now in Athens, and is a very fine actress. She is married and has a child. She is still very beautiful.

VJY: And Charlotte Rampling, for “The Cherry Orchard”?

MC: She wasn’t my first choice. There were circumstances around other choices for the part, but in the end she is perfect for the part.

VJY: The image of the rustic village cart -- decorated with bright village weavings as they still exist today -- as it rumbled into view bringing Iphigenia for the supposed wedding to Achilles remains with me today.

MC: The rustic cart existed in antiquity. If I had used a gold chariot, the context would distance the viewer from the human immediacy of the story. The rustic trappings of everyday life convey the timelessness of the story.

VJY: And the starkness of the Greek countryside had great impact, as well.

MC: Yes. The stones, the olives, are eternal. The eternal is integrated into what you do. It’s always been that way.

VJY: Here’s an ordinary question: What will be your next creative endeavor?

MC: I never plan ahead. I’m always open. Of course, I am always considering many scripts, etc. I’m always working. I work all the time. I write and translate.

I have translated three of Shakespeare’s plays into Greek. It’s totally absorbing.

VJY: Which of all the awards and honors you have won made the biggest impression on you?

MC: The first one. The Edinburgh Film Festival in 1953. Because it was the first. The first time for anything makes it the most important.

VJY: In what ways do you feel your work is meaningful to the Greek American community?

MC: I don’t think that it is meaningful. When my films were shown at the Paris and the Plaza theatres here, no one came. I don’t think they are very aware of my work or care very much.

VJY: I came.

MC: No you didn’t. You’re too young.

VJY: I was there, and so were many of my friends.

MC: Yeia sta niata sou.

VJY: What do you think is the best way to nurture and expand a talented child ‘s creativity?

MC: Of course it depends on a child’s interests. If a child is interested only in football, you can’t make him become a musician. Parents can have a negative influence on a child’s creativity by insisting on compliance with their own desires for the child. If a child shows a talent for a creative art, he will pursue it himself. If he really wants it, he’ll find a way. If he is motivated he will seek it out himself. The individual must do it himself.

The prolific Michael Cacoyannis, director of 15 films, directed 15 plays in Greece and 10 plays in the United States since 1954 (including the 1983 Broadway revival of the musical based on his film, Zorba the Greek), and directed a total of 7 operas beginning in 1972. In 1979 he began translating Shakespeare’s plays into Greek and as of the date of this interview had completed 3. Mr. Cacoyannis also wrote a collection of essays, 2 screenplays, and translated an ancient Greek tragedy into Modern Greek and another into English as of the date of this interview.