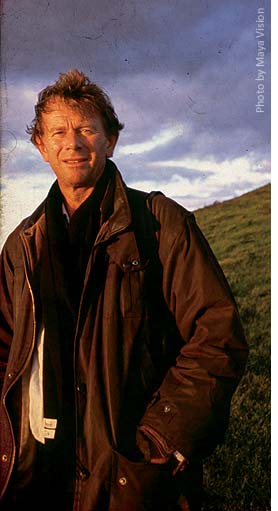

Trekking the globe to discover the epic of Greece: A conversation with documentary filmmaker Michael Wood

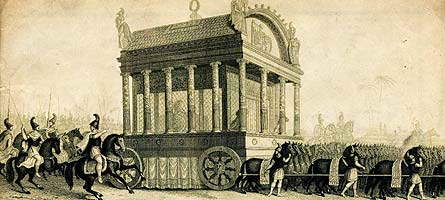

Among the documentaries he has created and hosted for worldwide audiences and shown here on public television, British historian Michael Wood has followed the travels of heroes for his In Search of the Trojan War, the trek of ancient pilgrims from Athens to Eleusis in "The Sacred Way," and his most ambitious journey so far: the 20,000-mile epic of conquest In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great. "Since I was a child, I have always been fascinated by the story of Alexander," says Wood, who holds postgraduate degrees from Oxford and has more than 60 documentaries to his credit. "It's an incredible story about one of the most dramatic events in the history of the world.”

Among the documentaries he has created and hosted for worldwide audiences and shown here on public television, British historian Michael Wood has followed the travels of heroes for his In Search of the Trojan War, the trek of ancient pilgrims from Athens to Eleusis in "The Sacred Way," and his most ambitious journey so far: the 20,000-mile epic of conquest In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great. "Since I was a child, I have always been fascinated by the story of Alexander," says Wood, who holds postgraduate degrees from Oxford and has more than 60 documentaries to his credit. "It's an incredible story about one of the most dramatic events in the history of the world.”

Any modern hazards you faced retracing Alexander's journey?

Well, you can't go into Iran, or places like that, without getting permission in advance. You can't just arrive, you have to have visas. It's only in a country like Afghanistan, where things have broken down, that a certain amount of negotiation is needed between internal frontiers. And, for instance, we wanted to get a helicopter to take us over the city of Tyre and the helicopter was in the Israeli-occupied zone in south Lebanon. That takes a bit of negotiation.

Were you ever in danger?

Kabul was under siege when we went there and we did have armed guards. More risky, perhaps, was taking the helicopter out of the Israeli-occupied zone in south Lebanon simply because it was a very volatile situation. But I never felt in danger of anybody's hostility towards us. I mean, something could go wrong, and there could be a point where you think, "God, I wish we had not put ourselves through this." But that happens more because of the sheer arduousness of this physical terrain, you know, sickness, weariness. I remember we had a terrible journey through one mountain in Pakistan, and the descent at night was around 5,000 feet down, it was precipitous, there was this tremendous storm, and everybody was absolutely weary from several days of tracking, and I think it was at this point that Lynette, our camera assistant, threw her bag down and said, "Stuff Alexander the Great, I never want to work with the guy again." But you'd make documentaries at home if you bothered about things like that.

How much has the landscape changed in 2,500 years and were you able to get an authentic feel of the obstacles he faced?

Yes, I mean, obviously the further you get away from the Mediterranean, the more you go back to the kind of conditions that, in some ways, might resemble what he saw. And, obviously, that helps: It helps from the point of view of the film, if you were walking through modernity it would be difficult to convey a sense of the living past. Whereas you can convey something of that in some of these wild places. And it gives you yourself, the traveler, a great sort of feeling of that as well. I remember when we crossed the Hindu Kush mountains on the Khawak Pass, the feeling of being absolutely in his footsteps and seeing what he saw, conditions he went through, that was great. You really got a buzz from that.

Did your impression of him change after the journey?

I think you get the feeling you know somebody better having walked a mile in their footsteps, or walked 20,000 miles in this case. I think I got a much closer impression of the sheer verve, determination, and all that risk-taking, that kind of calculation, the discipline of it, all sorts of aspects of the way he did things. In terms of his actual character, I think I still think what I thought before, you know, that all the traditions about him were right: He was all the things he said. And I think most of all, you've got to remember he's a man of his time and that, sure, he might well have purged families of his closest colleagues, and he might well have had the expedition's chronicler executed, and so on, but he was a man of his time. Probably anybody under that kind of pressure, thousands of miles away from home, in hostile territory, would have reacted with absolute ruthless decision against any possible threat. I think there's probably a degree to which he was corrupted by power, but there were other aspects of his character that were incredible: He was exciting to be with, he was thrilling to travel with, he incited great loyalty in his troops and love, he was chivalrous and generous. But I can't say I warmed to him.

Why is that?

I tended to identify with the people whose lands he went through and the people who spoke against him.

Isn't that a modern interpretation?

Oh, I'm sure it is. But the last thing we want is people like him in the world. People like Alexander were destroyers of people and cultures in the end. My personal regret over the last twenty years in all these travels is that the world is homogenizing and we're losing all these things. I think global civilization can be taken too far, if you like, but I think it's an inevitable process.

Have you always been interested ancient Greece?

I've always been interested in Greece. I first hitched around Greece when I was eighteen and it's extraordinary. When you look at the great civilizations in history, obviously the most influential have been China, India, Islam perhaps, and Greece. But of the ancient civilizations, (the most influential were) China, India and Greece. And China and India were vast civilizations that covered almost continents. But Greece is a tiny country, tiny, yet nothing in human history matches the sheer spread, reach, brilliance of the Greek story. What they did in every branch of literature, science, philosophy, is an incredible story. And it's not only part of our roots, but part of the roots of the Muslim world as well, their culture spread across western Asia. So it's a fantastic story, it's an amazing story, and it's a process that just didn't happen two thousand five hundred years ago, it carried on, it had long antecedents, it flowered then, it then spread through Alexander's successors, it crossed much of Asia, it regenerated itself under Byzantium, the last tiny bit of Greece was occupied for four hundred years by an oppressive colonial regime, but tiny bits of it still came down to modern times. It's a great story.

What made you do the story of the Trojan War several years ago?

I did a series about the Dark Ages in Britain and these semi-legendary figures like King Arthur, Alfred the Great, and so on. And when we did that, and I've always been interested in Greece, I had this idea of doing something on the Greek dark ages, which of course, are much earlier, and about the tale of Troy. It's a relationship between archaeology and history and documentary and fact and fiction.

How do you document myth and fiction, which is a large part of the Troy tale?

Well, there's more to it than that, because, obviously, Bronze Age Greece did exist, the archaeologists did uncover a lot of these sites that were made famous in Homer and had been important in the Bronze Age, even though they became insignificant later on. And, most important, the diplomatic archives of the Hittites actually does refer to the Greeks and does refer to a situation that seems similar to Homer's situation. And, also, you discover how poets like Homer actually construct and pass down their tales. Television is good at telling stories and what's great is if you can lead the audience in a quest and the audience can make their own conclusions and you lead them on and show them what possible answers exist. So, if you are interested in that kind of thing, as I am, then those were the kind of films that seemed interesting to make.

Was your journey to Eleusis also a quest?

I just decided, having done a few big journeys of various kinds in my life already, that I would do the opposite and do an anti-travel film, which was just a walk through twelve miles of industrial highway. The device of the film was to show that even through twelve miles of industry and modernity, it was possible that the past still somehow percolated through the people and the landscape and the story. And, of course, it happened to be a journey that was much more significant to that culture than most journeys that you could ever do today.

As a historian, do you regret how much the world has changed since ancient times?

Well, that's the nature of history and the nature of life. There's no point regretting it, that's life. Sure, one can regret that Eleusis was destroyed and it didn't come down to modern times, but it's futile to regret it, really. What interests me is the connection between the past and the present and whatever lives in the present.

How has your work been received in Greece and other Greek communities throughout the world?

How has your work been received in Greece and other Greek communities throughout the world?

I think there was a certain amount of enjoyment of the Trojan War, which was shown in Greece and reviewed in the papers. But they're very, very touchy about Alexander the Great. I've had Greek criticism because of this whole business about Macedonia. I did a talk in Chicago and there were people in the audience saying, "Why did you call them Macedonians?" And there were people saying, "Why did you call them Greeks?" (Laughs) You can't win. "You call him Alexander of Macedon, but Macedonia is not Greek!" And you say, "Well, hang on a minute, if you're suggesting that we all have to change what we called these people for two thousand years just because some state decides to call itself Macedonia, that's your problem, mate." The Greeks can look after themselves, I think.

Any future films with Greek subjects?

Well, yes. I really would like to do a series on the Greeks. I've written a series which not only looks at the classical legacy, but the continuity of the Greek experience from the ancient times to the modern day.

What is the status of the project?

I wrote a treatment for it, and I talked to public television about it and, as always, you're in the hands of your backers. You could get funding for it. Obviously, the important thing, though, is to keep intellectual control. What you can't have is somebody saying, "Oh, you can't say that about Macedon." That's the real problem. But that has nothing to do with somebody like me, because, obviously, I've been going to Greece for thirty years and I love Greece. And what interests me about it is also the survival--you see, it's not going to be very much longer now that you can actually film surviving living connections. The older generation of Greeks who lived through the civil war and the thirties contain a knowledge in their brains that is not transmittable, almost. They know things that have been passed down and you need to get at that before it goes. If you go down to Mani in the Peloponnese even now you can find old women who can do the old lamentations for the dead. I remember in the time that we were filming the Trojan War with a friend whose family came from Mani, going to the room in one of these old towered villages where an old lady was dying and she spoke this archaic Greek. So it won't be much longer.

You said the Greeks survived a "cultural holocaust" during the Turkish occupation?

That's putting it too strongly, but you know, the Greek culture did survive under the Turkish rule, but it had a hard time. And there was an intellectual culture which survived elsewhere. The printing of Greek books was all moved to Italy and the intellectuals like Koraes were in Paris, with a lot of the European supporters. But it's what survives in the ordinary people that really interests me: the customs, the rituals, the language, the beliefs, the lamentations, the tales, and most of it has not been recorded.